When it comes to sustainable development, people who call themselves realists ask: if the house is catching fire, why should we be measuring the temperature? Surrendering to this self-fulfilling prophecy is, however, not what individuals or leaders should be doing.

The stove is set on 9, but there is still time to prevent a disaster. Our survival is at stake, threatened by short-sighted policies. We know where the world should be in a decade’s time – we have 17 Global Goals for this – but in order to get there, we first need to understand where we are in absolute terms, as well as the trajectories we are on. The SDG Index and Dashboards are powerful tools for policymakers and advocates; we applied them, for the first time, to the 22 Arab countries. The results of this study constitute a wake-up call.

Activating the Science-Policy Interface

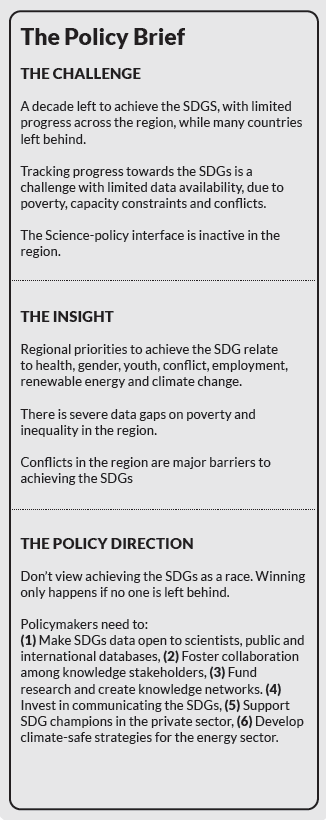

Data is a crucial driver of policy in many areas, but too often it is used to justify pre-existing choices or the continuation of business as usual policies. In environmental policy, the role of science is fundamental. Social policies too require large amounts of disaggregated data to inform economic policies that support equality and welfare for all. In countries that struggle with socioeconomic and security problems, availability of even basic socioeconomic data is often challenging. Poverty, human capacity constraints, conflict and violence create vicious cycles that effectively counteract efforts to improve data-driven policymaking.

Most countries do not leverage data and science sufficiently for policymaking. The classic example is climate science: we all know how little carbon we can still emit before reaching a point of no return, and we have the technologies and policy tools to act accordingly. For many climate-vulnerable countries, this timeframe for global action is ten years, as noted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report from 2018 on global warming of 1.5°C.[1] Still, no government in the world has yet been able to take the bold and speedy steps needed to decarbonize its economy in line with science. This is perceived to entail prohibitively high economic and social impacts. Electoral cycles do not combine well with policies that have higher front-end costs, no matter how significant their long-term benefits.

Enter the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Celebrated as a rare success of multilateralism, the SDGs are 17 interlinked, indivisible and universally-applicable goals contained in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which the UN Member States agreed to in 2015.[2] All countries have signed onto this aspirational agenda and are expected to reach these goals by 2030. The understanding embedded in the Agenda is that developed and better-off countries should support the poorest and most vulnerable to ensure that "no one is left behind." This motto also applies within countries, as well as regions.

The SDGs have been in implementation for four years now, and there is a decade left to achieve them. UN reports show improvement in many areas on a global scale.[3] These include reducing extreme poverty and child and neonatal mortality, improving access to electricity and safe drinking water, and expanding terrestrial and marine protected areas. However, there is great concern over slow progress overall. We are not on track to achieving broader targets on poverty and hunger eradication, gender and income equality, biodiversity conservation and preventing dangerous climate change. Conflicts and instability as well as intensifying natural disasters are complicating efforts to focus political attention on sustainable development. As underscored by UN Secretary-General António Guterres at the UN High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development in September 2019, despite progress, "we are far from where we need to be. We are off track".

Measuring Progress towards Sustainable Development

So how do we know where we are? Tracking global progress on sustainable development is not always an exact science. There are 169 official SDG targets and 232 unique indicators that governments have agreed and that constitute the global indicator framework for measuring progress on the SDGs at the global level.[4] However, as of December 2019, only half of the official indicators had an established methodology and data for at least 50% of countries. Another challenge is that almost half of the 169 SDG Targets are not quantified, which makes their tracking difficult – examples include targets to support R&D of vaccines and medicines, or substantially reduce youth unemployment.

Similar to their efforts at the global level, UN agencies conduct crucially important work at the regional level to map whether we are on track towards the 17 goals.[5] A progress report on SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) produced by the UN Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) in 2019 found that, while progress in access to energy has been positive in many Arab countries, the region is not on track on the two other targets – renewable energy and energy efficiency, and the Arab Least Developed Countries (LDCs) "lag far behind the rest of the region."[6]

National governments are also monitoring progress, as they have the primary responsibility for following up and reviewing progress. Sixteen Arab countries have already prepared their Voluntary National Review reports to present at the UN High-level Political Forum.[7] These reports serve to highlight progress at national and sub-national levels, support the integration of the SDGs into national decision-making processes, and drive the inclusion of civil society and other stakeholders in development planning. However, they do not contain quantitative indicator frameworks for tracking progress and trajectories.

So where should Arab governments start? First, invest in data: data gathering and dissemination are crucial areas for the region’s governments to invest in. Second, open up data: at the same time, while data "trickles up" from national statistics offices to the international SDG indicator custodian agencies, governments also need to make data available to the public. Third, use the data for research and development: governments should work with local universities and research institutions to improve existing data and develop further ways to measure sustainable development that are relevant for the national and regional contexts, as sustainable development looks vastly different from one place to another.

With only a decade left to achieve the SDGs, important gaps in both availability and accessibility of data hinder efforts by the region’s governments and other stakeholders to evaluate where they stand in implementation and how fast they are progressing towards the goals – or, in some tragic cases, away from them. So how can we overcome these challenges?

The Case for Region-specific Indices… and their Challenging Journey

Since 2016, the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) and Bertelsmann Stiftung have published global-level SDG Index and Dashboard reports that seek to fill the current gap in data for policy-making.[8] The global Indices are based on approximately 100 indicators that are as closely aligned as possible with the official SDG indicators and fill remaining gaps with data from reputable international databases and scientific studies.

The SDSN has also begun encouraging and empowering its regional and national networks, which together comprise more than 1,200 universities and research institutions worldwide, to develop SDG indices that tailor the global-level methodology to regional and sub-national contexts. SDSN has so far produced reports on Africa, Europe and European cities and US cities in partnership with members. Most recently, the Emirates Diplomatic Academy, as the regional hub of SDSN, partnered with the Network’s secretariat to develop the first Arab Region SDG Index and Dashboards report.[9]

How is this Arab Region SDG Index different from the global one? When examining the global index, we observed major gaps in data availability for the 22 Arab countries in some areas, and a number of region-specific priorities and challenges, which were not sufficiently covered, including:

- Diabetes prevalence (SDG 3)

- Tertiary school enrolment and school test scores (SDG 4)

- Female to male gross national income (GNI) per capita (SDG 5)

- Degree of integrated water resources management (SDG 6)

- Renewable energy output of total electricity output (SDG 7)

- Labour freedom, youth unemployment, and export product concentration (SDG 8)

- Fossil fuel pre-tax subsidies per capita (SDG 12)

- Ocean health for fisheries (SDG 14)

- Battle-related deaths, status of human rights treaties, and political stability (SDG 16)

As a starting point for our indicator selection, in order to avoid bias due to missing data, we required a minimum coverage of 75% for inclusion in the regional index – in other words, data had to be available for at least 75% of the 20 Arab countries with a national population greater than one million. Palestine, which faces major data availability challenges (see further below), was also not considered when calculating for minimum coverage. We conducted an extensive search of international and regional databases and studies, and were able to come up with 30 new indicators for this first regional index. After removing indicators from the global index with insufficient data coverage, we ended up with a total of 105 indicators. Over time, the regional index will evolve to include new indicators as data availability improves.[10]

Drawing from regional expertise is crucial for ensuring relevance for the region. For this first index, we conducted two expert consultations, which gave us a number of useful ideas about aspects of sustainable development that Arab countries should be measuring. In our May 2019 web-based consultation, we received more than 200 individual comments, containing suggestions for possible new indicators and validating indicators we had already identified. In the majority of cases, however, we were unable to find data that would fulfil the five criteria for inclusion: relevance for the region; statistical adequacy, or validity and reliability; timeliness; data quality; and 75% coverage. In our August 2019 consultation we reached out to thematic experts who helped tremendously in validating the final selection.

The indicator selection process provided two important takeaways: first, the 22 Arab countries urgently need to address the most significant gaps in SDG-related data, which relate to SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). There is a major dearth of data in social indicators relating to poverty, income and wealth distribution, and labour, much of which must be gathered by governments through administrative surveys. In order to enable at least some of the region’s countries to receive a Goal-level score on these SDGS, we included data for poverty headcount and the Gini coefficient despite low coverage: 13 countries and 15 countries, respectively.

Second, while we tried to disseminate our call for the expert consultation widely via social media and institutional networks, personal networks still provided the highest response rate. Regional academic and research institutions, even within a single discipline, work in highly-fragmented ways and this applies in many cases on the national level as well. Despite the wide diversity of socioeconomic circumstances across the Arab countries, a number of common denominators – language, history, culture, identities, geopolitics and various environmental and natural resource-related factors – tie the region closely together. Not being able to fully leverage the power of academic collaboration and expert networks in the region to support sustainable development policy-making is a significant lost opportunity. Efforts are underway to build these networks from the bottom-up, but Arab governments will need to provide enabling conditions for the science-policy interface to function and flourish. It is time for stakeholder engagement in sustainable development policymaking and implementation that goes beyond cosmetic box-ticking exercises. Ownership of policies and their implementation only comes from meaningful engagement, which also helps prevent disenfranchisement.

And the Winners (and Losers) Are…

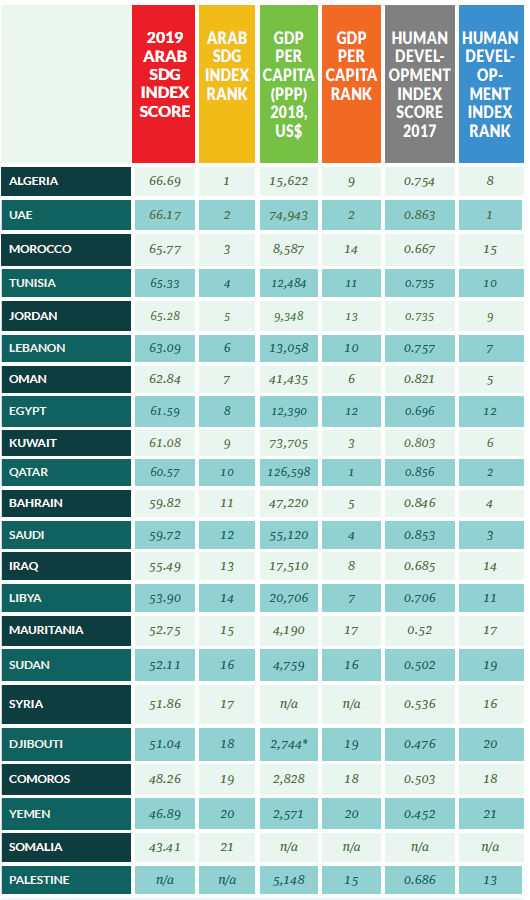

So, which were the best-performing countries in the 2019 Arab Region SDG Index? The top-five-performing countries, with a total score of 65 or above – meaning that they are approximately two-thirds of the way to achieving the SDGs –, were Algeria, the UAE, Morocco, Tunisia and Jordan. Taken as a whole, the Arab region received an average score of 58.

In this exercise, however, the most important thing is not who gets the highest score – in the SDGs, what matters is getting everyone across the finishing line. On this account, the region does not appear in a favourable light: collectively, the 22 Arab countries receive a ‘red’ traffic light score for 51% of the 17 SDGs, indicating that they are far from achieving these Goals. The region’s six LDCs and two other countries suffering from conflict, Syria and Iraq, each have more than 10 SDGs in ‘red’. It is also important to keep in mind the significant differences in population size across the Arab region’s countries: there are 11 countries with a population of more than 10 million, together comprising 89% of the region’s population. Egypt’s SDG performance alone (ranking eighth, with a total score of 62 in 2019) will apply to the lives of almost one-fourth (23%) of the region’s total population.

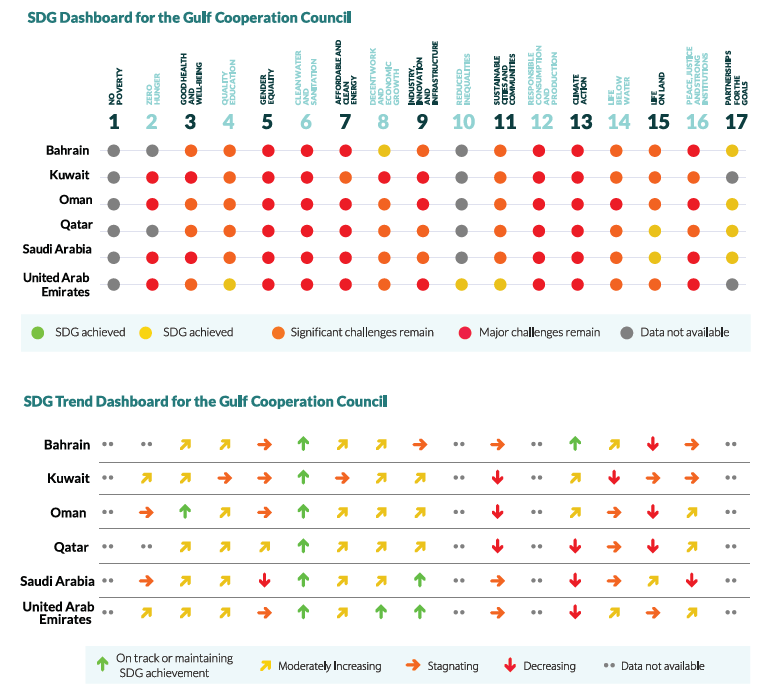

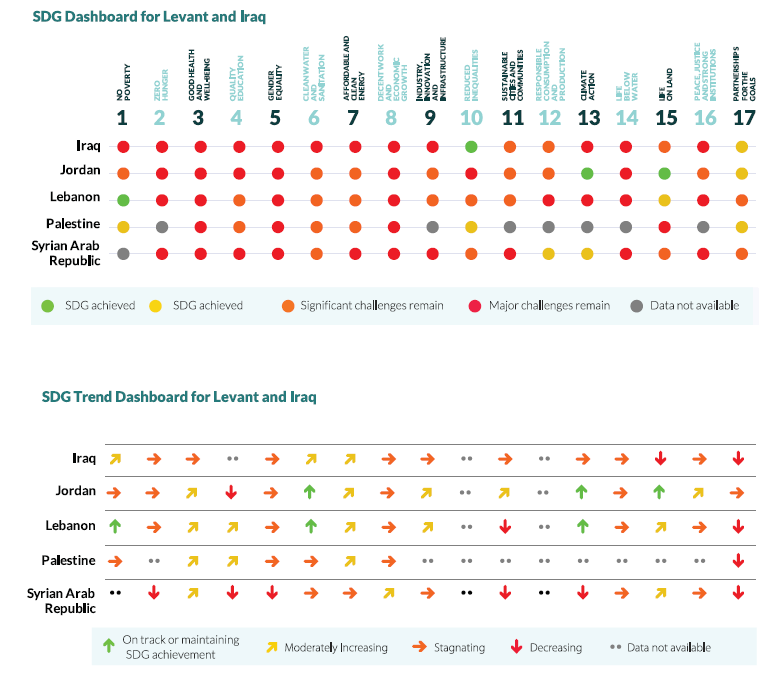

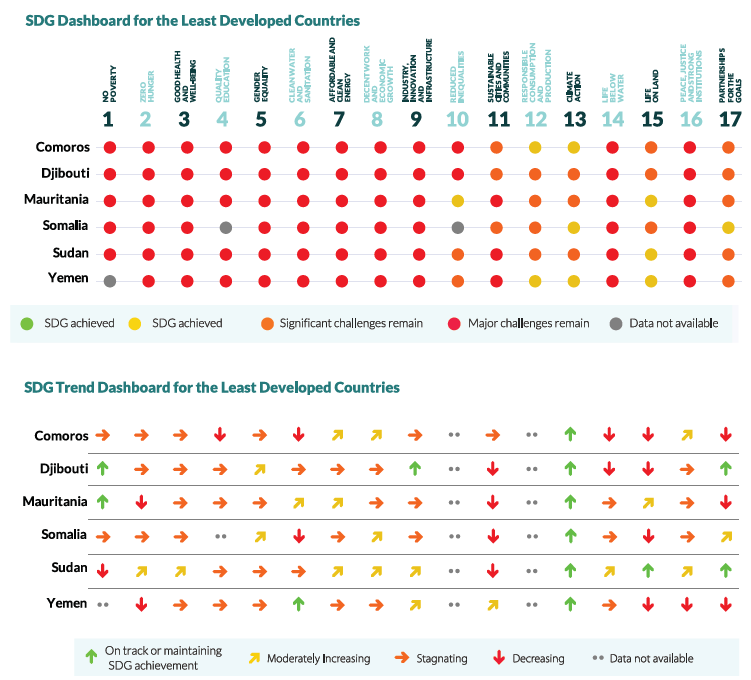

The study consists of two main components: a score and colour for current performance, as well as a colour-coded arrow for trends over time. The SDG index assigns a score (0–100) and a traffic light colour (green, yellow, orange, or red) to indicate performance on both indicator and SDG level. Green rating denotes SDG achievement and is assigned to a country on a given SDG only if all the indicators under the goal are rated green. Yellow, orange and red indicate increasing distance from SDG achievement. When calculating SDG-level scores, red, which indicates major challenges in achievement, is only applied if both worst-performing indicators score red.

In the 2019 Index, all Arab countries with sufficient data received a red score on SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 5 (Gender Equality). The Index also indicates significant challenges in several other Goals: SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being); SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation); SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy); SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth); SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure); SDG 14 (Life below Water); and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).

The SDG trends dashboards, in turn, measure trends in goal achievement for those indicators where data for multiple years is available. Here, there is some slightly better, if not outright positive, news. The data available indicates that several Arab countries are on track to achieving SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 13 (Climate Action). There are also moderate increases in performance across several SDGs, including on health, energy and infrastructure. Even here however, data gaps may hide some remaining challenges (or successes): trend data for SDGs 6 and 13, for example, was available for indicators on drinking water and sanitation services and per capita carbon dioxide emissions, but not for freshwater depletion, sustainable water management or climate change vulnerability. On these latter indicators, there is a possibility that trends may be deteriorating.

For analytical purposes, we also divided the 22 countries into four groups based on geography and income:[11]

- North Africa: The three most challenging Goals for this subregion (Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia) were SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). On SDG 2, all five countries scored red on the obesity indicator, and on SDG 5, all countries scored red in female to male labour force participation and income ratios. Rising trends were found on SDGs 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and 13 (Climate Action), while they are deteriorating on various others.

- Gulf Cooperation Council: The six GCC member countries (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi and the UAE) face major challenges on SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 13 (Climate Action). Significant data gaps complicated assessing these countries’ performance on social equity-related SDGs. GCC countries perform better on SDG 4 (Quality Education), SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 15 (Life on Land) where no country scores in red. Based on available data, however, all six countries seem on track to achieving SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) – which however, may owe to the fact that trends data is only available for a limited number of indicators, as noted above.

- Levant and Iraq: The four Levantine countries (Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine and Syria) and Iraq are the only group with goals in green in the SDG Dashboard, though progress is uneven as these goals are all different. All received red scores on SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). Data gaps – partly due to exclusion from some international databases and studies – greatly complicated measuring Palestine’s progress: data was available for only 55% of the 105 indicators for Palestine.

- LDCs: The six Arab LDCs (Comoros, Djibouti, Mauritania, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen) are in acute danger of being left behind in sustainable development. All countries receive a red score for all SDGs from 1 through 9, as well as SDGs 14 (Life below Water) and 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions). Positive indicator-level scores were related to certain aspects of health, waste, greenhouse gas emissions and spillover impacts on other countries. All are well on track to achieving SDG 13 (Climate Action). On other Goals, trends are mixed.

SDG Achievement, GDP Per Capita and the Human Development Index in the 22 Arab countries[12]

Changing Course: The Positive Feedback Loops of Science and Policymaking

Much has been said in environmental policy circles about ecological tipping points, which "lead to abrupt and possibly irreversible shifts between alternative ecosystem states, potentially incurring high societal costs".[13] Scientists agree that, on our current trajectory, even if all current Paris Agreement emission reduction pledges were implemented, we are headed to well over 3°C of global temperature rise compared to the pre-industrial era. This would, with a high likelihood, destabilise ecosystem equilibria worldwide, turning our planet into a "self-heater" and make life as we know it unsustainable.[14]

Less known as a concept are social tipping points, which labour rights advocates at a 2019 UN Climate Change Conference in Madrid described as events that "put in danger community-level support for the climate change policies we need." People will not support environmental policies if they are perceived as socially unfair, resulting in unemployment or unequal price hikes. In recent years, calls for good governance and just transitions have risen rapidly worldwide, along with the awareness about the urgency of tackling climate change and other environmental crises.

There is also a growing recognition that science needs to be put at the centre of policymaking so as to avert the looming disasters. However, without making data and science accessible to both citizens and governments, science remains in the ivory-towers of universities and social media echo chambers of like-minded minorities.

So what can the Arab region do to avert both ecological and social tipping points and bring everyone along in the needed transformations? Drawing overarching policy recommendations from our first regional SDG Index is difficult, partly given the diversity of the region in terms of SDG performance. Policy responses need to be grounded in each country’s circumstances. Governments, together with stakeholders, need to develop an understanding of national-level priorities – something for which the regional index can only serve as a starting point.

From the process of preparing the first Arab Region SDG Index and Dashboards, we can, however, extract some recommendations for governments on how they can leverage the potential of data and science to inform policymaking for sustainable development:

- Focus on data for the SDGs: Improve data availability and, most importantly, accessibility for scientists and the public. Provide data for international databases and urgently fill data gaps for social equity indicators.

- Foster collaboration with, and among, knowledge stakeholders: Create processes for integrating experts and institutions producing sustainable development-relevant knowledge into national policymaking and planning. Fund solutions-oriented research and development. Foster the creation of knowledge networks that generate actionable knowledge for SDG implementation.

- Invest in sustainable development communication: Build capacity and awareness across the government sector on the SDGs. Work with scientists and communications professionals to make science accessible and policies understandable to the public. Integrate the SDGs into school and university curricula.

- Align investments with science and the Global Goals: Support SDG champions in the private sector and incentivise companies to integrate sustainable development into business operations and strategies. Develop long-term strategies for the energy sector that are in line with climate-safe trajectories, and align investments in the broader economy with the SDGs.

In order to reach the SDGs in the Arab region, we need to focus our attention on turning off the sparks of regional conflict and also on the underlying development drivers that require urgent attention before the house truly starts catching fire. Our children and future generations demand it. As pointed out by ‘Midnight Oil’ in their song ‘Beds are Burning’: "the time has come, a fact’s a fact, it belongs to them, let’s give it back."

Mari Luomi is Senior Research Fellow at the Emirates Diplomatic Academy and the lead co-author of the 2019 Arab Region SDG Index and Dashboards Report. Read full bio here.

Endnotes:

[1] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report: https://www.ipcc.ch/2018/10/08/summary-for-policymakers-of-ipcc-special-report-on-global-warming-of-1-5c-approved-by-governments/

[2] The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld

[3] See for example: https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/74/4

[4] SDGs Tier Classification: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/iaeg-sdgs/tier-classification/

[5] A regional sustainable development report by ESCWA was due to be published around the time of the writing of this article.

[6] Energy Progress Report in the Arab Region: https://www.unescwa.org/publications/energy-progress-report-arab-region

[7] More on the Voluntary National Reviews: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/vnrs/

[8] The SDGs Index and Dashboard: https://sdgindex.org/

[9] Arab Region SDG Index and Dashboards report 2019: https://sdgindex.org/reports/2019-arab-region-sdg-index-and-dashboards-report/ (English version) and https://sdgindex.org/reports/2019-arab-region-sdg-index-and-dashboards-report-(arabic)/ (Arabic version).

[10] Unfortunately, we were unable to include any data from regional databases or surveys. Regional databases, including by the UN Development Programme’s Arab Development Portal and Islamic Development Bank’s data catalogue, either contained data from international databases (to which we already had access) or from national statistical offices. Regional comparisons, in turn, require harmonized datasets. Subregional databases like the GCC-Stat only contained data for a smaller number of countries. Specialized regional agencies produce useful data, but in many cases it is outdated for the purposes of tracking the SDGs, whereas surveys, such as the Arab Barometer and the Arab Youth Survey, either do not cover all Arab countries or they disclose scarce information about their methodologies.

[11] Charts originally published in: Luomi, M., Fuller, G., Dahan, L., Lisboa Båsund, K., de la Mothe Karoubi, E. and Lafortune, G. 2019. Arab Region SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2019. Abu Dhabi and New York: SDG Centre of Excellence for the Arab Region/Emirates Diplomatic Academy and Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

[12] Originally published in: Luomi, M., Fuller, G., Dahan, L., Lisboa Båsund, K., de la Mothe Karoubi, E. and Lafortune, G. 2019. Arab Region SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2019. Abu Dhabi and New York: SDG Centre of Excellence for the Arab Region/Emirates Diplomatic Academy and Sustainable Development Solutions Network. Data sources: GDP per capita data from World Bank World Development Indicators and HDI data from UNDP, retrieved in October 2019. *) GDP per capita data for Djibouti is for 2011 (latest available year).

[13] Ecosystem tipping points in an evolving world: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-019-0797-2

[14] The Planet Is Dangerously Close to the Tipping Point for a ‘Hothouse Earth’: https://www.livescience.com/63267-hothouse-earth-dangerously-close.html

You must be logged in to post a comment.