How can policies generate impact? Many governments know how to pass laws but struggle to execute those laws. They successfully legislate to build schools but children still aren’t learning. Why? What are the capabilities governments need to go from successfully delivering policy products to actually fostering real policy impact? This is the question addressed here. Using data from multiple case studies, we offer a list of key capabilities for yielding policies with impact. Based on these capabilities, policymakers can use the Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) toolkit to develop policy responses with impact.

Capabilities for Policy Impact

How can public policy professionals make their policy interventions more successful on a regular basis? We teach policy implementation to some of the most committed and able public policy professionals in the world. Most of them want to know if management studies can offer any useful ideas to help them achieve their goals. They are not interested in nebulous thoughts offered from thirty thousand feet. Rather, they are looking for well researched, practical, actionable lessons that they can apply in the real world, to improve their personal capability to implement public policy.

These professionals’ most common concern is that while their governments are proving successful at delivering policy products, they are not achieving policy impact. These governments can pass laws and build schools and develop IT systems, but they struggle to ensure these products yield impact. Many laws are not executed, many schools do not promote learning, and many IT systems are not used. As a result, many of the problems that policies are meant to address are not being solved.

This concern raises the following question: What are the capabilities needed by governments to successfully foster policy implementation impact? Put differently, we need to identify public policy implementation impact capabilities. The Building State Capability Program at Harvard University defines public policy implementation impact capabilities as "the empowered abilities of government agents to bring responses to citizens’ problems to full impact (where the problems are sustainably managed or resolved)." [1] So how can we identify such capabilities?

How Should Policymakers View ‘Policy Implementation’, ‘Impact’ and ‘Capabilities’?

The definition of ‘public policy implementation impact capabilities’ in the section above focuses on characteristics of people and organizations (or agents). To be more specific, these do not include more general conditions that determine success but rather what agents need to be able to do to foster policy success. ‘Capabilities’ differ from ‘skills’, ‘competencies’ or ‘capacities’. The latter concepts relate to things that individual agents are able to do. These are personal abilities that often accrue from training. ‘Capabilities’ are the abilities that agents (people or organizations) are actually empowered to do extrinsically (where they are authorized to act) or intrinsically (where personal choice inspires action). These capabilities are represented in the demonstrated actions of agents.

Capabilities as Empowered Abilities

Implementation here takes a broad view. Implementation does not happen after planning, but rather it involves every part of the delivery and impact process—from problem identification, through planning and to final review. The question here becomes: How can these abilities be developed, empowered, and connected? This is what policymakers need to figure out. But how?

Policies are responses to problems, and policy impact success is actually the resolution of the problems that spark policy responses (or their sustainable management). This contrasts with views of policy as sets of ‘technical products’ (like laws) which may or may not be problem-driven, where "success" is seen as the delivery of these products. Public policy should be viewed as something that is crafted when citizens face problems they cannot solve without government, where the problem is the main instigator and motivator of policy engagement. As such, policy impact would be nothing less than the resolution (or management) of these problems.

What Key Capabilities Can Drive Impact of Public Policy Implementation?

How do we identify the capabilities governments seem to need to effect real impact (manage/resolve problems) through policy interventions?[2] This can be done by asking a simple question: "What actions did agents take that were seen as crucial to success?" Consider the case of Rwanda’s local government reforms where "a series of consultations about the government" took place with the aim of fostering a community discussion about concerns with public sector performance. This case suggests these actions were vital to policy success as they drew attention to the problem of local government performance and helped galvanize a community of supportive and engaged stakeholders.

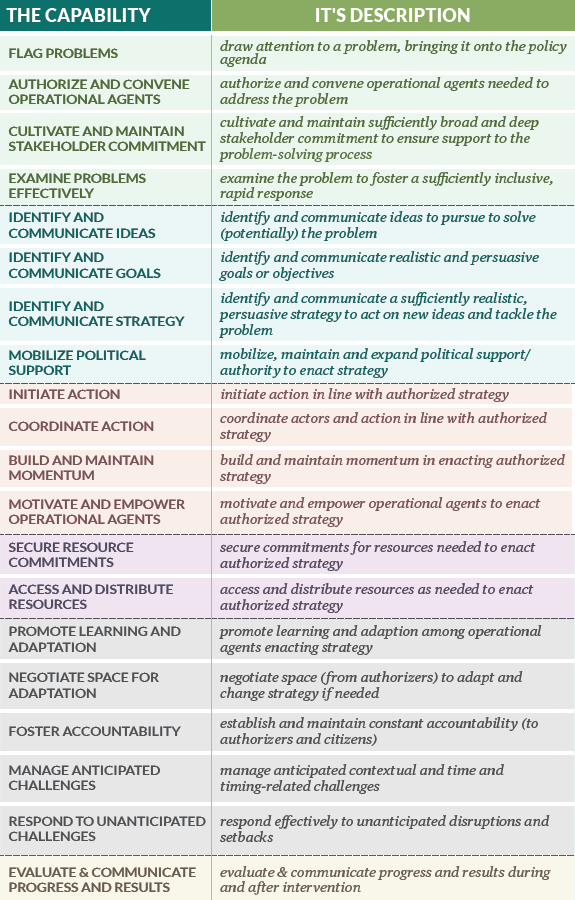

Once all such actions are identified, their descriptions can be clustered into categories, each representing a manifest capability associated with the achievement of policy implementation impact. For instance, the Rwanda example of consultation is common across many similar cases. If we put these all together, we can describe two key capabilities; 1) ‘drawing attention to a problem’ and 2) ‘cultivating sufficiently broad and deep stakeholder commitment to solve the problem’. Applying this approach across thirty similar cases of innovation generated a list of fifteen key public policy implementation capabilities (Table 1).

Table 1. Key Public Policy Implementation Impact Capabilities

The capabilities listed here suggest that the key to achieving policy impact is being able to manage uncertainty, complex problems, people, politics, and the vagaries of unexpected events.

It is important to emphasize that the order of listing should not be seen to imply that capabilities always occur at the same time in the implementation sequence. Actually, linearity is not a key feature of any of the cases. Most were interactive and iterative in nature (with multiple capabilities coming together at various times during policy narratives).[3]

A Practical Toolkit for Policy Impact: Exploring the PDIA

Most countries do not invest in the capabilities shown in Table 1. Rather, they focus on establishing more traditional administrative mechanisms emphasizing solutions based on planning, monitoring, supervision, and evaluation. Instead of investing in impact capabilities, many administrative mechanisms imply replacing messy politics with sanitized technical processes and simplifying uncertain and complex problems into neatly packaged solutions.

These more traditional administrative capabilities are useful in promoting the delivery of ‘technical products’ like laws and school buildings and strategies. However, they are not the ones that will generate impact of such policy products. Governments need softer, people-oriented, politics and context-sensitive capabilities to achieve actual impact in their policy implementation. How can they achieve this?

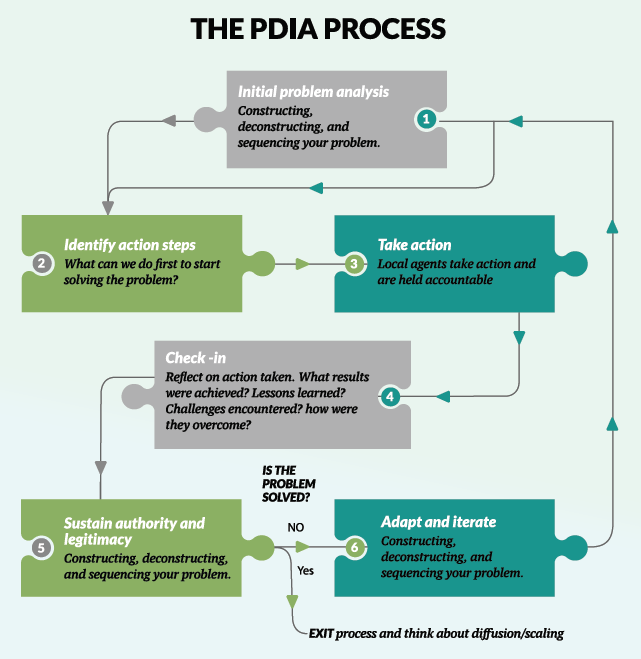

The Building State Capability (BSC) program has been testing such capabilities in applied research for a number of years and has developed a new approach to policy design and implementation that employs these kinds of key capabilities. This new approach, called Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA), provides a structured iterative, interactive approach that emphasizes capabilities like problem analysis, team building, active stakeholder engagement, management of political authorization, reflection and learning. It has proven successful in driving governments to achieve impact through these new capabilities in direct engagements undertaken by BSC in 13 countries[4]. Practically, policymakers can test the approach for themselves by utilizing the PDIA Toolkit.

What is the PDIA Toolkit?

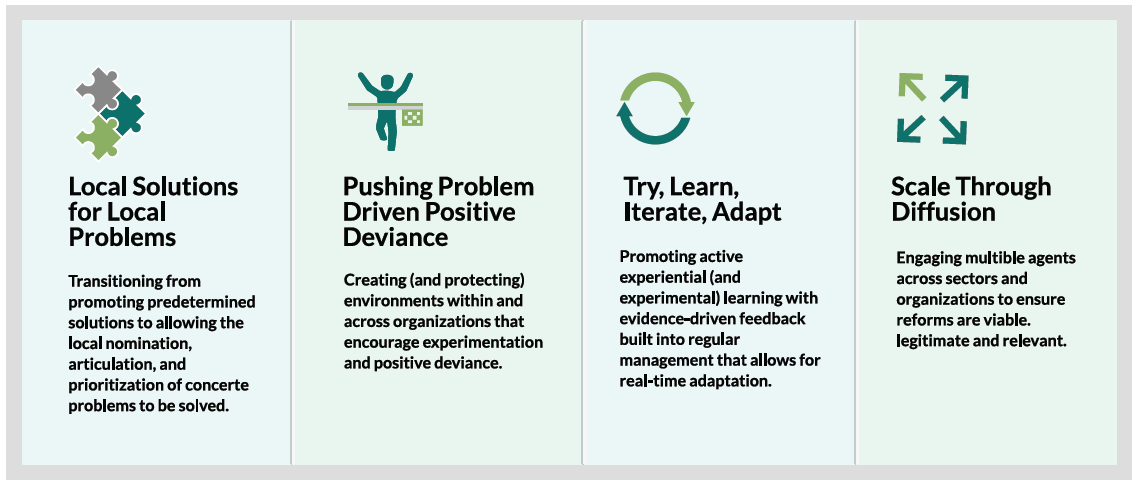

The Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) toolkit offers a framework and a method for policy professionals to do things differently. It rests on four principles:

1. Construct Locally Driven Problems

PDIA is about building capability through the process of solving good problems. It’s not about finding the solution and then replicating that solution; it places emphasis on the process of solving problems, not the solutions themselves. Historically, this is how today’s most effective organizations acquired, and now maintain their capability for implementation. It is not easy or without real risk as change processes inherently generate a contentious mix of "winners" and "losers". This is where the PDIA process is most useful, as ultimately it is a more sustainable approach because it infuses legitimacy into these change processes.

The process of problem identification is a long iterative process of diagnosing, testing and revising; the learning thus needs to be experiential, occurring in real time, with built-in rapid cycles feeding back into design and implementation. It requires taking calculated risks, embracing politics and being adaptable (thinking strategically but building on flexibility). Crucially, one needs the humility to accept that we do not have the answers and to accept, discuss and learn from failure.

2. Build and Maintain Authorization

To put PDIA into practice, it requires that agents receive authorization to do things that, in their current ecosystem, they are not allowed to do. It requires changes in an organization’s authorizing mechanisms and personnel structure to authorize a reform, to incubate it, and then to get it moving. But How does one gain and secure robust authorization?

This brings us to the topic of leadership. Given a specific project, who – notionally and actually – leads the policy process? On what basis is that person identified as a leader? Do they have access to adequate resources? To top-down authority? Implementing power? Rather than the traditional view of leadership – whereby projects seek to gain authorization through an individual champion, who is sufficiently high-ranking to help push through a proposed reform – reforms are never really led by one person alone. Indeed, this "hero orthodoxy" can actually be another source of failure in development. Successful change comes instead through multi-agent leadership. In this view, the cumulative and concerted efforts of a networked team (rather than any one leader alone) result in success.

" ‘Capabilities’ are the abilities that agents (people or organizations) are actually empowered to do extrinsically (where they are authorized to act) or intrinsically (where personal choice inspires action)"

3. Learn, Iterate, Adapt

The PDIA process helps governments escape the capability trap through a series of six-stage ‘find and fit’ iterations that are intended to foster the gradual but progressive identification and implementation of reforms.

Ultimately, in order to achieve policies with impact, policy professionals need to generate, test and refine context-specific solutions in response to locally nominated and prioritized problems; we need systems that tolerate (even encourage) failure as the necessary price of success.[5]

"Governments need softer, people-oriented, politics and context-sensitive capabilities to achieve actual impact in their policy implementation"

Matt Andrews is the Edward Mason Senior Lecturer of Economic Development at Harvard Kennedy School, working on questions of government effectiveness in the development process. Read full bio here.

Salimah Samji is the Director of Building State Capability at Harvard University’s Center for International Development. Read full bio here.

Endnotes:

[1] The discussion is based on the authors’ work on the Building State Capability (BSC) program at the Center for International Development (CID) at Harvard University. The program researches strategies and tactics to build the capability of public organizations to implement policies and programs. Through the program, the Authors teach policy implementation to some of the most committed and able public policy professionals in the world. For more visit: www.bsc.cid.harvard.edu

[2] The findings here are based on a case survey of thirty cases where an author saw real impact, drawn from Princeton University’s Innovations for Successful Societies (ISS) database. The case sample is diverse, so that policymakers from various backgrounds, and facing various policy challenges, would feel that their realities (or something close) are represented. The author scrutinized each case to gather detailed qualitative information about capabilities that were manifest through the actions of agents. Further details on the sample and the methodological details of the analysis are available in: Andrews (2015). Andrews, Matt, 2015. "Explaining Positive Deviance in Public Sector Reforms in Development," World Development, vol. 74, pages 197-208.

[3] The ISS cases (used in the authors’ study) are written as linear narratives, and this influenced how the capabilities were ordered. The first capability, for instance, tended to be the first capability referenced in each case: Agents had power and ability to draw attention to a problem, bringing it onto the policy agenda. The last capability was similarly mentioned as the last ‘empowered ability’ in many cases: Agents had power and ability to assess and evaluate progress and success during and after their intervention.

[4] These include: Albania, Central African Republic, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Honduras, Liberia, Lesotho, Mozambique, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, South Africa and Sri Lanka. To learn more visit: https://bsc.cid.harvard.edu/projects

[5] More information on the PDIA toolkit is available at: https://bsc.cid.harvard.edu/. The toolkit is made available in Arabic in collaboration with the Dubai Policy Review here: https://bsc.cid.harvard.edu/files/bsc/files/2020-bsc-pdia-toolkit-ar.pdf

You must be logged in to post a comment.