How did Singapore, a small island in South East Asia with no natural resources, become one of the most developed countries in the world? How did its system of government and policy structures produce one of the most celebrated economies and thriving societies worldwide, in a matter of a few decades? What is the secret sauce of Singapore? One need look no further than its main ingredient: meritocracy. Through a unique combination of policies that prioritize merit over any other quality, Singapore has developed an equitable education system and an advanced civil service that ensure government effectiveness, national productivity, sustainable development and societal cohesion. Meritocracy has been the tide that has lifted all boats.

Singapore is absurdly small. When it became independent in 1965, it was only half the size of Bahrain, or one-tenth the size of Dubai. It has no natural resources – no oil, no natural gas, and no minerals to be mined. Adding to that, Singapore gained its independence in a turbulent region and at a turbulent time. To complicate matters further, it was home to a multi-ethnic population: 75% Chinese, 15% Malays and 8% Indian, with a whole mixture of religions: Muslims, Christians, Hindus, Buddhists, Taoists and others. This combination of factors led many observers to believe that Singapore would fail, whether due to external pressure or internal turmoil.

Against all odds, Singapore has become one of the most successful states in recent human history, improving the living standards of its people faster and more comprehensively than any other state has ever done.

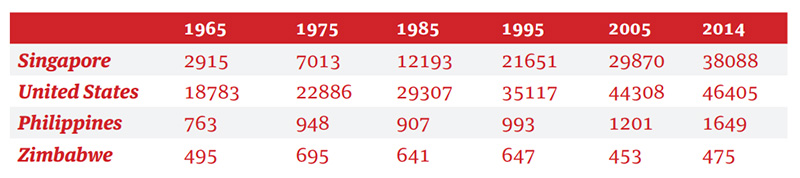

Table 1: Comparison of real GDP per capita

How did Singapore do it? The answer is, of course, complex. It includes many factors: exceptional leadership, the peaceful ASEAN ecosystem, geopolitical luck, sound public policies and an effective and competent public service. Lee Kuan Yew, the nation’s founding Prime Minister, has said that "to get good government, you must have good men in charge of government". The Singapore government has consistently acted on that belief, co-opting the best into political leadership and creating a pipeline of talent into the civil service through the scholarship system.

One key reason for Singapore’s exceptional success, against all odds, was its ability to extract and exploit the human potential available in its small population. This was aided by an emphasis on economic rationality over political expediency. Policy lessons learned from the Singapore experience can be replicated in other states, big or small.

Managing Human Capital the Singaporean Way

Some key assumptions lay behind the policies that Singapore designed to extract human talent. The first assumption is that some people are more naturally talented than others. The second is that exceptional talent and ability can be found among the poor just as among the rich. Following this line of thinking, the third assumption is that the state can proactively search for, and develop, talent among its population. Important factors such as education, health and quality of life can unlock human potential leading to greater individual and collective achievement. For these reasons, the Singaporean government has focused on implementing public policies to provide these essential goods to all its citizens. In short, good public policies can develop a well-functioning meritocratic society.

The search for talent in all sectors of society may appear to have been driven purely by pragmatic considerations. In reality, it was also driven by ethical considerations. The key founding fathers of Singapore, especially Lee Kuan Yew, Goh Keng Swee and S. Rajaratnam, described themselves as democratic socialists, and their concern for the poor was the result of a deep moral commitment to equality. Paradoxically, this moral commitment delivered golden economic results. This is the main reason why Singapore, a nation with no natural resources, has accumulated more foreign reserves per capita than almost every other nation in the world. In addition to economic growth, meritocratic policies also delivered social and political stability. The poor felt an equal sense of ownership over positive outcomes as did the rich. This helps explain why the ruling party of Singapore is the longest serving elected government in the world. Meritocracy delivers many positive results for any society, not least a growing sense of citizenship and national identity.

The Merits of Education

The first set of public policies that built the foundation of meritocratic Singapore is its educational policies. Singapore’s education system is based on the principle that each child is talented in his or her own way. Within this perspective, the academically gifted are streamed into the same classes while other students with technical or vocational abilities are streamed into relevant fields. Grouping students of similar capability makes for effective teaching even when the classes are large. Mistakes do happen. I was streamed into a technical school, learning metalwork and woodwork. I failed those subjects. I was then streamed into the arts stream where I excelled and got a scholarship to go to high school and the National University of Singapore. Since I come from a poor family, I could never have gone to these higher education institutions without government scholarships.

In contrast to many other countries around the world whose economists and politicians are effectively sourced only from the highest echelons of society, Singapore looks for economic stars even among the desperately poor. Two successful Ministers for Trade and Industry, Lim Hng Kiang and Chan Chun Sing, came from very poor families. In most societies, they would not have risen to such ranks. In Singapore, government scholarships enabled them to succeed.

Singapore employs a competitive test to ensure that only the best minds get the prestigious government scholarships. The recipients of these scholarships are expected to apply and get admitted into the top universities of the world, and are expected to maintain their status, graduating at the top of their classes. As a result, the best performing Singapore students get a disproportionate share of admissions into highly ranked universities, including Stanford, Harvard, Columbia and Berkeley.

One shocking statistic indicates how well Singapore has done with its education system. The country that sends the largest number of non-British candidates to Oxford and Cambridge is, of course, China, the world’s most populous country with 1.4 billion people. Amazingly, the second largest number comes from Singapore, which has a population of 3.4 million citizens. In short, there is a global market test to confirm that Singapore’s meritocratic policies are actually extracting the most from Singaporean society, despite its talent base being small in absolute terms.

The Secret Ingredients of Singapore’s Civil Service

When the government-funded scholars graduate, they are expected to work for the government for five to eight years. Traditionally, many Asian societies are hierarchical. Equally traditionally, in most governments, promotions are based on seniority, not merit. Singapore does the opposite, and as a result, very young people can assume senior positions. When I was appointed Ambassador to the UN at the age of 35, my British counterpart was astonished. In the British Foreign Service, you can only be a First Secretary at the age of 35. In that service, the boss is never younger than his subordinate. In Singapore, it is common to have younger bosses. When I was 40 years old, I worked for a Minister who was 35 years old. In short, seniority does not count in Singapore. Merit does.

Singapore did not invent meritocracy. The leaders of Singapore simply asked which organisations in the world were most successful and why. The answer they got was that private sector companies were often more successful. At that time, Shell Oil Company offered a useful example. They were successful because they promoted their staff on merit, not seniority. It was on this basis that the Singapore civil service became the first ex-British colony to switch its promotion policies away from the British civil service system to that of a British oil corporation system.

When I was the Head of the Singapore Foreign Service, I was asked to rank all Singaporean diplomats on the basis of their "HAIR" qualities. "HAIR" stood for Helicopter vision (the ability to zoom in on details while understanding the broader, strategic context), Power of Analysis, Imagination and Sense of Reality. The "HAIR" system was developed by Shell Oil Company to identify their best talent worldwide. Singapore has now improved on the "HAIR" system; its talent selection processes are comparable to those of the most successful organizations in the world, including McKinsey and Harvard University.

The corollary of the rapid promotion of the talented is the demotion and redistribution of the untalented. In most civil services of the world, a job comes with life-long tenure. In the Singapore civil service, there is no similar job security for those being groomed for the most senior positions. Hence, these civil servants who are consistently ranked at the bottom of their cohort are encouraged to leave (although efforts are made to do this in a humane fashion).

In Singapore, political connections do not help civil servants. The salaries of the top civil servants are among the highest in the world, the result of the policy of matching civil service salaries to what the civil servant could, on average, have earned if he or she had instead chosen advancement in the private sector. All civil servants are assessed annually on their performance and their potential; decisions on their promotion, bonuses and salary increments are made on the basis of these assessments. Very few civil services award bonuses. In Singapore, bonuses make up an important part of the remuneration for senior civil servants. There is therefore relatively little discretion for supervisors to "play favourites" or to hire or promote someone ahead of others who are abler. The scope for politicians and other powerful individuals to influence hiring or promotion decisions in the civil service is also very limited.

These policies of meritocratic promotion and competitive market salaries also result in practically zero corruption in the Singapore Civil Service. When cases of corruption do occur, the government penalizes offenders seriously. Again, in contrast with other states that have great natural resources at its disposal, Singapore has developed some of the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world with virtually zero leakage, while others who have earned billions of dollars from oil exports have squandered these billions, funnelling them into private pockets.

To prevent corruption, the public sector’s procurement decisions are also based on merit and, specifically, the ability of the vendor to meet clearly stipulated requirements. Government purchases mostly require competitive tenders, with the default set at awarding the contract to the lowest bidders. This ensures value-for-money and reduces the likelihood that contracts would be awarded to politically connected firms or individuals. While public officials can recommend that a vendor that has not put in the lowest bid be awarded the contract, they have to justify their recommendation on meritocratic grounds, meaning that they have to demonstrate that awarding to the higher-priced vendor would deliver better public value than awarding to the lowest bidder would.

The social and political benefits of meritocratic public policies are as potent as the economic benefits. Meritocracy also means that employers, whether in the public or private sector, hire and promote people without ethnic or gender discrimination. In Singapore’s multi-ethnic society, this lack of ethnic discrimination also results in multi-racial harmony. Each ethnic group, no matter how small, has a chance at the most coveted jobs in Singapore. Since selection is based on merit, not race, the Singapore population was unfazed when at one point in time, the President (S. R. Nathan), Senior Minister (S. Jayakumar), Minister for Finance (Tharman Shanmugaratnam), Minister for Law (K. Shanmugam) and Minister for Community Development, Youth and Sports (Vivian Balakrishnan) were Indian, despite Indians only making up 8% of the population.

The Challenges of Meritocracy: Drawbacks and Fixes

The Singaporean system is not perfect. Despite its successes, it has been subjected to critique by Singaporean citizens themselves. Professor Kenneth Paul Tan of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy has written recently: "Today, the Singaporean idea of meritocracy is criticized for entrenching structural limits on mobility; for its overly narrow idea of merit and success; and for an increasingly self-regarding elite that seems too interested in staying in power and that citizens perceive as arrogant and unresponsive to their needs."

Such criticism is considered vital and healthy for a highly successful system like Singapore’s civil service, as success often breeds complacency. The political leadership of Singapore has also recognized that these concerns have to be addressed. The Minister for Education of Singapore, Mr. Ong Ye Kung (who came from a poor family himself), acknowledged in Parliament on 11 July 2018 that although "there is no contradiction between meritocracy and fairness," it "is recently in danger of becoming a dirty word" as it "seems to have paradoxically resulted in systemic unfairness." Mr. Ong acknowledged that there continued to be an achievement gap between rich and poor: "Unlike the first generation of Singaporeans where students are mostly from humble backgrounds, the next generation is pushing off blocks from different starting points, and students from affluent families have a head start."

Mr. Ong’s comments reflect the public’s growing concern about inequality in Singapore. Policies aimed at meritocracy, if not implemented with sufficient concern for different starting points, can in fact exacerbate inequality. It is therefore even more important for the government to ensure that its meritocratic policies actually provide the opportunities for all its citizens that would reduce, not exacerbate, inequality. Indeed, in response to these criticisms, the government has continuously tweaked its meritocratic policies, beginning to address children’s needs from preschool, as those children from poorer families do not start with the advantages of those from better-off families. In response, the resources devoted to pre-school education have been significantly stepped up in recent years. The lesson here is that no system is perfect. Every system requires continuous improvement.

While it is not perfect, there is no doubt that compared to its counterparts worldwide, the Singapore civil service is ranked among the best in the world, if not the best. The result of this high-performing meritocratic civil service is that Singapore outperforms most societies in almost every human development indicator. Singapore is ranked 9th globally in the 2018 UNDP Human Development Index.

This is the ultimate paradox of meritocracy. In theory, it creates the best-performing elites. In practice, it has been shown to enhance the wellbeing of all sectors of society. Hence, while the elitism of meritocracy will generate some tensions, these tensions can be managed and lead to enhanced social well-being and human welfare.

Kishore Mahbubani, is a Professor in the Practice of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore, and the Founding Dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy. Read full bio here.

End Notes:

1. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/in-theory/wp/2016/04/16/how-singapore-is-fixing-its-meritocracy/

2. https://www.moe.gov.sg/news/speeches/parliamentary-motion-education-for-our-future–response-by-minister-for-education–mr-ong-ye-kung

3. http://hdr.undp.org/en/2018-update

You must be logged in to post a comment.