What forms of leadership does the world need in the era of the fourth industrial revolution? In a time of unprecedented change, leaders— in both the public and private sectors— must enhance their adaptive capacity in order to lead their organizations and countries through times of uncertainty. The most pressing challenges facing organizations today have to do with their capacity to adapt policies, processes, regulations and products to constantly changing realities. Learning to distinguish between adaptive challenges and technical problems is essential for dealing with disruptive changes and external pressures. Developing and nurturing adaptability requires a new kind of leadership or at least a new emphasis on certain leadership behaviors. Tackling adaptive challenges requires exercising leadership as opposed to authority, mobilizing discovery, tolerating losses, and generating innovations and new capacity to thrive.

"May You Live in Interesting Times"1

We are in a period of rapid change and radical transformation that no one alive has experienced before and perhaps has never occurred in all of human history. Fundamental breakthroughs abound: Artificial Intelligence (AI), machine learning, Blockchain, computing power, sharing economy, Internet of Things (IoT), 3D printing, nanotechnology, big-data analytics, visualizing technologies (VR & VI), brain research, and biotechnologies are opening vast new possibilities and concomitant risks. These rapid scientific and technological advancements, what has been recently called the "Fourth Industrial Revolution", has dramatically bent the arc of history, and will alter political, economic, social, environmental, and security dynamics, fundamentally changing the global landscape.

In his book, "The Future", former US Vice President Al Gore, writes that "There is no prior period of change that remotely resembles what humanity is about to experience. We have gone through revolutionary periods of change before, but none as powerful or as pregnant with the fraternal twins — peril and opportunity — as the ones that are beginning to unfold."

What if the world we have been experiencing is the "new normal"? What if we and our children better get accustomed to it? What would it mean for the way we live our lives? In short, what are the implications of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, for you, and your family, your organization and your community? And what would leadership look like under these conditions? How will it be different than leadership in the past?

To answer these questions, begin by exploring how this revolution is unlike its predecessors. While many scholars and futurists differ on its implications, almost everyone agrees that the current era is different in two distinctive ways:

Velocity of Change

First, these current life-changing scientific and technological advancements are evolving at a mind-boggling rate. The speed of change is unprecedented.

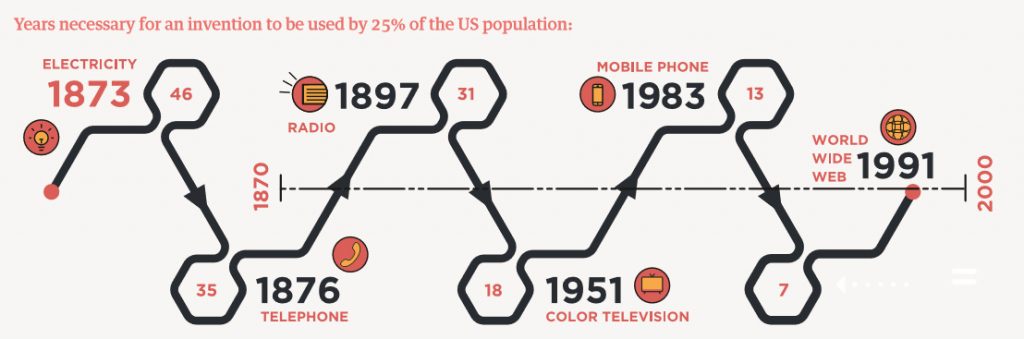

The US National Intelligence Council’s 2012 global trends report compellingly makes this point. The Council analyzed the number of years necessary for an invention to be used by 25 percent of the US population: it took forty-seven years for electricity back in 1873 and thirty-five years for the telephone back in the 1870s, while the internet took only seven years in the 1990s.

Look at the advancement of microchip processors and computing power for an even more dramatic example. Today’s Intel-Core i7 processor has a speed of 4.60 GHz, roughly six billion (yes with a B billion) times faster than the first one invented less than 50 years ago. Today’s iPhone Xs has a million more computing power than the first computer invented back in 1975.

Revolution Not Evolution

Second, is the disruptive nature of these exponential life-changing technologies. Today, the biggest accommodation provider, Airbnb, owns no hotels; the biggest taxi company, Uber, owns no cars; the largest retailer, Alibaba, has no inventory; the most popular media company, Facebook, creates no content; and the fastest growing currency, Bitcoin, has no nationality. Each of these innovations has turned established industries upside down. Business as usual is dead.

The emergence of extreme populist political parties suggests that this Fourth Industrial Revolution might disrupt not only industries but also economies and societies at a faster pace than those economies and societies can adjust, potentially creating more chaos and turmoil and limiting our capacity to grasp available opportunities.

Technical Problems and Adaptive Challenges

In a world where it is entirely possible that for as long as we can look ahead, change is the only constant and the future is uncertain, unpredictable and volatile, what does this mean for you? How do you exercise leadership under these conditions? How will you have to change your behavior to survive and thrive with inadequate information for decision-making and relentless transformational change?

There are two core leadership skills which have always been useful, but are now essential: 1) enhancing your capacity to face and meet new realities, and 2) having the courage to take responsibility for creating the future. Both are critical in order to survive and thrive in this new world.

Your family, your organization, your community and your country need you to be successful at enhancing their adaptive capacity and agility in facing difficult challenges and grasp emerging opportunities. If you aspire to exercise leadership in this new reality, you must have the courage to take responsibility for creating the future by driving change rather than being driven by it.

This is not an abstract idea, in In our work with organizations from the public, private and nonprofit sectors all over the world, the most pressing challenge facing them today is the capacity to adapt their policies, processes, regulations, services and products to the constantly changing external pressures. , this is not an abstract idea. When When the external changes outpace individual and collective ability to adapt, then the trajectory is all downhill. As Darwin stated, "It Is not the strongest of the species that survive, but the most adaptable".

Developing and nurturing these two core skills will require a new kind of leadership or at least a new emphasis on certain leadership behaviors. First and foremost, leaders need to help their organizations and communities identify their adaptive challenges and distinguish them from technical problems.

Indeed, the single most common cause of leadership failure is that people, especially those in positions of authority, understandably try to treat adaptive challenges as if they were technical problems.

This is why today we see more routine management than leadership in our organizations and communities. What’s the difference?

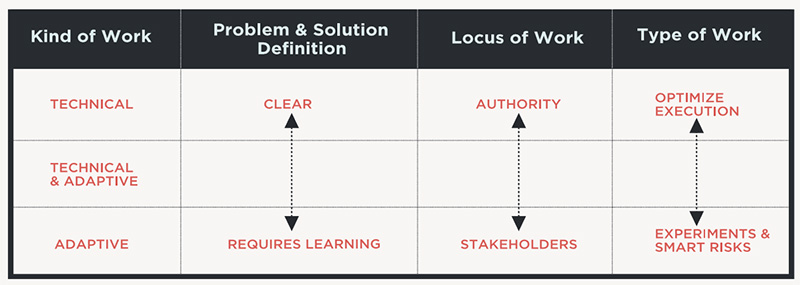

Technical problems may be very complex and critically important like replacing a faulty heart valve or fixing a broken arm or a malfunctioning IT system or creating a performance management system. These all have known solutions that can be implemented by current know-how and best practices. Each of these problems may be beyond your skill set to solve. However, you know someone, a doctor or an IT expert or a management consultant, who can bring knowledge and authoritative expertise to the issue and very likely resolve it. Technical problems reside above the neck, in people’s brains and logic systems.

However, if the challenge is not that of faulty heart valve or a broken arm or a malfunctioning IT system, or ineffective performance system but instead obesity or high cholesterol or shifting a government entity’s role from a service delivery to a service supervision, then the IT expert, or doctor or management consultant are not adequate. Authoritative expertise or the exercise of authority will not ensure progress. The "problem" lives below the neck, in people’s hearts, habits, identities, beliefs, loyalties, and fears. The problem is not primarily technical in nature; it has elements of adaptive challenges which need to be addressed to move forward. Adaptive challenges can only be addressed through changes in people’s hearts, habits, beliefs, priorities, and loyalties. Making progress on adaptive challenges requires mobilizing discovery, tolerating losses, and generating innovations and new capacity to thrive.

Problems do not come neatly packaged as either "technical" or "adaptive." They do not arrive with a big T (technical) or A (Adaptive) stamped on them. Most problems come mixed, with the technical and adaptive elements intertwined.

While working with a government entity in the Gulf region that had adopted a new strategy to shift its business model from service delivery to service supervision, it was clearthe authors realized that part of the challenge was to help them distinguish the technical elements of the issue from the adaptive challenges.

The technical parts of this challenge were to establish legal agreements, quality assurance frameworks/manuals and performance monitoring systems to govern their relationships with the new service centers to make sure that services delivered at the highest standards. To deal with the technical issues, they conducted benchmark studies, visited other countries to acquire best practices and hired subject-matter experts to help in the process.

The adaptive challenge was that for many of the service delivery employees, this new strategic direction meant giving up something they genuinely cared about, namely delivering the services. For them, providing these services was part of their identity and how they define themselves. If they decided to stay in the service delivery business at these centers, they would risk losing their job security at the government and become part of an NGO or even a private company.

For those people, the movement from delivery to supervision was a huge adaptive challenge. They were being asked to give up something they love and learn new skills and competencies. There were no quick fixes; time, effort, resources, and empathy were needed to preserve these people’s motivation and passion for the work they do while helping them learn new capacities.

When an organization hires a consulting firm, applies best practices, invests heavily in additional resources and the challenge persists, then you know that the issue is not a technical problem but an adaptive challenge. We believe that the greatest waste of organizational resources is when people in positions of authority treat adaptive challenges as if they were technical problems, tending to default to easy solutions. Applying best practices feels good because the organization is doing something that has worked elsewhere. However, as Einstein once stated: "The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting different results". If you want different results than what you are getting, you need to do things differently and successful adaptation require experimenting with new practices and different ways of doing things.

What Makes Adaptation So Difficult That People Avoid It?

The challenge of adaptation is at the heart of much of the lack of success of leadership initiatives. Adaptation comes from evolutionary biology, in which successful adaptation has three characteristics; 1) preserving the DNA essential for survival; 2) giving-up the DNA that stands in the way for progress and 3) develop new DNA to make progress and thrive in the future.

Think of animal or plant adaptation. When a plant or an animal species adapt, some of the DNA (typically only about 4-6%) is left behind to make room for new DNA. Easy enough. However, when an individual, or an organization, or a family or any human community adapts, that DNA which is left behind (a practice or behavior or habit or belief) might mean the world for them. It is part of their identity, and what they tell others about themselves or see when they look in the mirror.

The adage: "People resist change" is not quite true. People love change when they know it is a good thing. No one gives back a winning lottery ticket or a significant promotion to a position of power. What people resist is not change per se, but loss.

What makes adaptation so difficult is that it entails loss, and this helps explain why people in positions of authority tend to avoid exercising leadership in these cases. When change involves real or potential loss, people hold on to what they have and resist the change.

Another case is based on our experience working with a government in the region that wanted to reduce its dependency on oil by diversifying its economy. They hired a world-renowned consulting firm to guide them in the process and draft a policy report with recommendations. Then, they developed a twenty-year long strategy with an ambitious vision. Three years later the government realized that the policy report and strategy alone were not enough. They needed to pay attention to their people, to help them move through the period of loss, and reinvent themselves with new capabilities. Finally, we were invited to design and develop leadership programs for nearly 500 of their core civil service professionals to be delivered over a three-year period. Realizing that this new strategy in itself was a huge adaptive change not only for the government but also for citizens and for the private sector, we designed the leadership program around real-life individual and organizational leadership challenges, while developing their diagnostic capacity. This work required courageous conversations among themselves to identify current practices that they need to leave behind (losses) and to distinguish the technical problems from the adaptive challenges. Then they were encouraged to design new experiments around to do the adaptive work.

In this case, the toughest adaptive challenges were around creating trust, fear, and confusion about the new vision and how they fit within it. They were waiting for instructions from their superiors to tell them what to do and how to do it. The required intervention, then, was to develop new competencies to help them take ownership of the new vision, and enhance their sense of shared responsibility. In time, there was a behavioral shift. Employees demonstrated more willingness to engage in difficult conversations about tough personal and organizational issues, establishing new cross-departmental initiatives and joint projects. Today, this government managed to substantially reduce its oil dependency and is vigorously working towards achieving its ambitious vision.

If the common factor generating adaptive failure is resistance to loss, a key to leadership, then, is the diagnostic capacity to find out the kinds of losses that are at stake in a changing situation, from life and loved ones to jobs, wealth, status, power, relevance, community, loyalty, identity, and competence. Once those losses are defined, the next step is to design and run smart experiments to help people go through that period of loss. Leading adaptive change is akin to acting as a grief counsellor.

A well-known example of adaptive failure is Kodak. Its board of directors refused to launch the first consumer digital camera which they had invented, fearing that it would affect their film market from which their profits came. They refused to accept short-term losses and disrupt their business model. By the time they embraced digital reality, it was too late, and Kodak filed for bankruptcy in 2012.

In this context, we believe, leading successful adaptive change becomes about the ability to leave behind what stands in the way of progress and take the best of your history into your future.

Distinguishing Exercising Leadership from Exercising Authority

Exercising adaptive leadership is radically different from doing a job really, really well, or from holding a high position of authority. How many people in positions of authority (Politicians, CEOs, managers) that you know have failed their communities, organization and followers to address their toughest challenges and generate progress? The list can be long.

Yet many ordinary people have made an extraordinary impact in the world. ; to name fewhHere are just a few who come quickly to mind, Mohandas Gandhi of India, a politician and lawyer who managed to mobilize his entire nation against the British with no formal position of authority, no title;in fact, he never had a title. Muhammad Yunus, a banker and a Nobel Peace laureate who pioneered the concepts of microfinance, changing the lives of millions of people around the world and . Malala Yousafzai, a child activist and the youngest Nobel Prize laureate who refused the ban of girls from attending school in the Swat Valley of Pakistan and her advocacy grown into an international movement.

For more such extraordinary cases from the Arab world, we can examine the stories of the winners of the Arab Hope Makers Award2: Nawal Al Soufi of the refugees’ lifeline in Italy, Hisham Al Dahabi, the golden heart of Iraq, the White Helmets of Syria, Mama Maggie and Ma’ali Al Asousi for their humanitarian work in Egypt and Yemen respectively. A common feature among all these people was that they seized the opportunity to exercise leadership to make a difference without having a position of authority or power.

Taking risks without having formal authority on behalf of a deep purpose is a common feature among all these people. It is helpful, then, to look at leadership as an activity, not as a person in a position of power, as leadership can be exercised with or without formal authority.

People tend to confuse and conflate leadership with authority. This is an old and understandable habit because authority provides three critical functions: 1) Direction, 2) Protection and 3) Order. In any role you play, whether as a parent, manager, CEO, or even as a president, you have a scope of authority that derives from your authorizers’ expectations that defines your job description. As long as you meet those expectations in your job description, your authorizers (your family, Board of Directors, Boss or People voted for you) are happy and will reward you in the coin of the realm, whether it is, a bigger job, a bigger salary, or an award (Ironically, one of the ways people are rewarded for never exercising leadership is, being called "a leader").

The leadership moment comes when doing the right thing would conflict with your authorizers’ expectations and when doing what people need from you is different from what they want from you.

Exercising leadership for adaptive change requires challenging people’s expectations, especially of those who love you the most, while doing so at a rate they can absorb.

A well-known example of the distinction of exercising leadership as opposed to exercising authority comes from right here in the Arab region, in the person of the late Sheikh Zayed Al Nahyan, the founder and first President of the United Arab Emirates, and Sheikh Rashid Al Maktoum, First Vice-President and Ruler of Dubai in their role in creating the most successful unification of different tribes/states in the Arab World. They brought together seven different tribes/states into one country back in 1971.

Before 1971, Sheikh Zayed had no formal authority over any other state or emirate but his own, Abu Dhabi. He believed that the greatest challenge facing his region was the division into small tribal states. If they could unite under one flag, he thought, they would thrive, flourish and achieve great success. It took him years of hard work to move the other heads of states toward his dream. His unification efforts were not part of his mandate or job description as the ruler of Abu Dhabi and indeed were not part of the expectations of his authorizers’ (People of Abu Dhabi). By nature, the people of Abu Dhabi would expect him to put all his energy to focus on their welfare, but yet he challenged their expectations and managed to mobilize them to support his unification efforts. Leading this adaptive change was extraordinarily difficult work. They experienced many setbacks, but they knew that if they were to succeed, the results would be profoundly meaningful. Forty-seven years later, Sheikh Zayed’s vision has led to the UAE being atop numerous developmental world rankings. People tend to respect and reward those people who are willing to take the risk of exercising leadership without authority.

What Should Leaders Do? Implications for Your Leadership

To summarize, if you are going to survive, thrive, and close the gap between your aspirations for yourself, your family, your organization and your community and the current reality, here are six practices which we would encourage you to try:

- Rather than focusing just on the execution of the mission, you need to put more emphasis on adaptation. Execution and adaptation are very different.

- Rather than being oriented to solve problems, you must begin to think of yourself as running experiments. Leadership is an experimental art.

- Rather than thinking of yourself as autonomous, think of yourself more as functioning interdependently, both internally and externally.

- Rather than responding to conflict by just working to resolve it, begin to see conflict as a leadership opportunity and more often as a signal of deeper value differences and explore and orchestrate it.

- Devote less time to searching everywhere for best practices, and more time to the courageous work of innovation, and exploration to invent next practices.

- Finally, rather than sacrificing your body for the cause, assume responsibility for taking care of yourself because you need to be at the top of your game to flourish now.

One fact we are sure of, you will not succeed in doing all these things from the first time or second time and in some cases not even from the third time, be prepared to fail, and embrace failure and learn from failure, as Mandela once said, "I never lose, I either win or learn". Every failure is a great source for wisdom from which we will learn new skills and orientation that fit with the rapid and transformational changes that are now part of our daily life.

We are at a historic juncture in human history, and each one of us has the opportunity and power like never before in history to shape the future. More than ever, the world needs individuals like you who believe deeply in their purpose to exercise leadership to help their families, communities, organizations and countries overcome their toughest adaptive challenges.

Marty Linsky is a Professor at the Harvard Kennedy School and the co-author of the best-selling book Leadership on the Line. Read full bio here.

Ghaleb Darabya is a Mason Fellow at Harvard Kennedy School and has taught at both Harvard Kennedy School and London Business School in their Adaptive Leadership executive programs. Read full bio here.

End Notes:

2- An initiative by The Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum Global Initiatives: https://www.arabhopemakers.com/.

Public Policy for a Digital Future.. Introducing The Dubai Policy ReviewAugust 7, 2020 7:12 pm

[…] Leadership in the Fourth Industrial Revolution […]