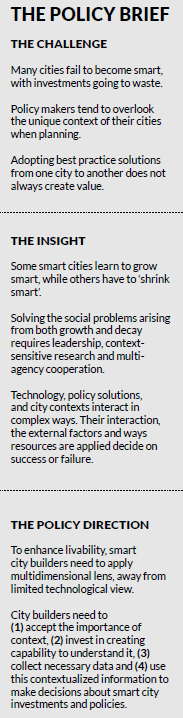

Cities throughout the world are changing. To respond to these changes, Mayors and other urban policy makers are investing heavily in innovations aimed at generating value for those who live and work in their cities; in a word, they are working to make their cities "smarter". Increasing pressures to make a city smarter as a way to respond to these changes are causing many city leaders to look to the world’s "smartest cities" for best practice solutions. Many of these solutions are based on "smart city technologies" and are driving significant investments. According to the International Data Corporation, a consultancy, smart city technology spend in 2016 was $80 billion, with $135 billion projected by 2021. The less told story is that many of these investments go to waste. So why do many of the smart city investments and solutions that prove widely successful in some cities, fail in others?

Unfortunately, many city leaders are finding that the direct adoption of an innovation from one city to another does not guarantee the creation of public value. They are finding that the high-pressure conditions to make their cities smarter quickly make it difficult for them to fully take into account the fact that no two cities are alike, and that what works in one city, may or may not be feasible in another. In other words, it is all about context.

How does context matter in smart cities development? According to Merriam-Webster, context is "the interrelated conditions in which something exists or occurs". Understanding the context of a city means unpacking and studying the challenges, capabilities, characteristics and successes of that particular city. It means investing in processes that examine the nature of the problems facing a city, the resources that a city has to draw on to solve its problems, and what stakeholders are looking for as solutions. It also means finding out why a smart city investment has or has not worked in other cities, and then using insight about how context has interacted with similar innovation efforts as input for decision making.

Investment choices are being made, in many cases, based on little understanding of why something worked in another city and what must happen in their own city for that innovation to create value. Cities where decisions are informed by a nuanced understanding of their own context are creating value. In other cities, the lack of attention to context is limiting the potential of smart city investments.

The questions before us are why are such important decisions about the future of the world’s cities still being made without critical consideration of context? And, what can urban leaders of tomorrow do differently to ensure that future investments create value for their cities?

According to the US-based nonprofit, Livable City[1], there are five fundamental aspects of great, livable cities: "robust and complete neighborhoods, accessibility and sustainable mobility, a diverse and resilient local economy, vibrant public spaces, and affordability". City leaders around the world are working to identify and close the livability gaps in their cities. Closing those gaps requires a variety of highly interdependent policy, management and technology innovations. How successful city leaders are responding to changing pressures on the livability of their cities relies to a great extent on their ability, or in many cases, their willingness, to invest in building an understanding of the specific context of their city. Unfortunately, building nuanced understanding of context can only happen by unpacking the complicated ways that the context of a city interacts with the problems a city is facing, the innovations expected to solve those problems, and the capability required to be successful. Taking the time to build that understanding is often at odds with the pressure on city leaders for quick decision-making. How can policymakers change this reality?

Growing Cities and Shrinking Cities – How Context Matters

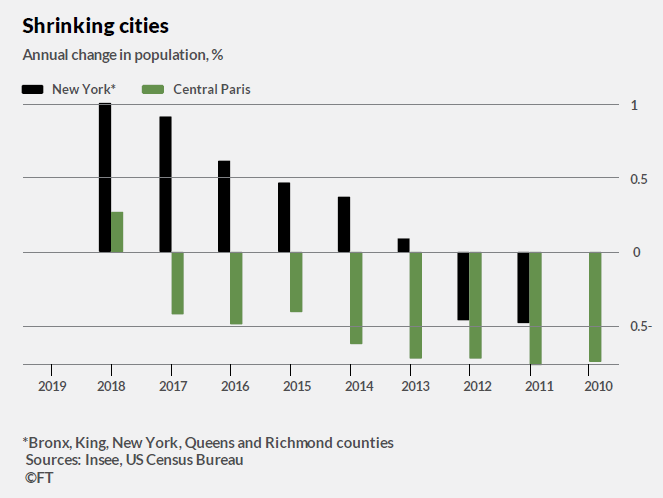

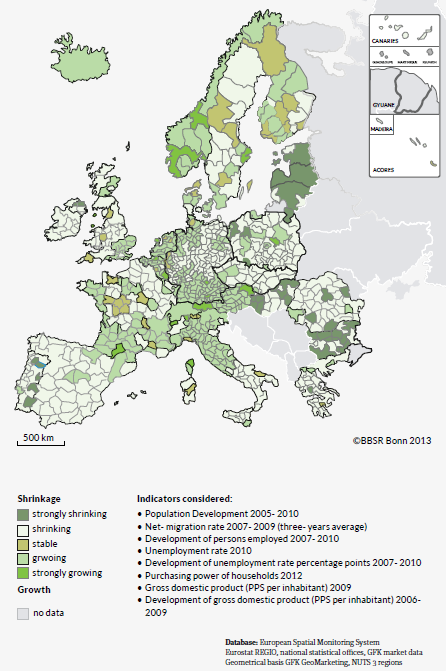

Urbanization and de-urbanization alike are impacting the livability of the world’s cities. Yet most writing about changes in the size of the world’s cities and the impact of those changes on livability are about growth. Almost any article on the global trend of urbanization presents one or another well-supported prediction about how by 2050 three quarters of the world’s rapidly growing population will live in cities, up twenty-five percent from 2010 and completely reversing the population distribution between urban and rural environments. This rapid growth, researchers and practitioners agree, is increasing pressure on the physical and social infrastructure of cities and straining the basic services that make a city livable. Social problems in such cities are recognized as increasingly complex and intertwined and their solutions require the collaboration of multiple city agencies, levels of government, nonprofit organizations, business, and society at large. Such growth-induced livability gaps have become the focus of Mayors and urban policy makers the world over and have been at the heart of smart city and urbanization research. In large part, smart city solutions put forward by industry are aimed at relieving the strain of growth on the world’s cities.

But there is another trend worth paying attention to. De-urbanization is also changing the context of many of the world’s cities and reducing livability in very different ways. While people are moving to cities, generally, to improve their quality of life, other factors are impacting cities, causing them to

shrink. Three main trends are leading to de-urbanization: declining fertility rates, as being experienced in Japan, declining manufacturing and mining, as being experienced in the US, and resource depletion and technological change, as being experienced in China[2]. While growing cities are struggling to modernize and expand their straining infrastructures, shrinking cities are struggling, to downsize their infrastructures and to find sustainable "financial models for operation and maintenance". Cities such as Sheffield, Iowa in the US and Ostrava in the Czech Republic are increasingly focused on how to "shrink smart"[3]. Policy makers must be clear about which strategies are right for shrinking cities and which for growing cities.

Can Cities "Shrink Smart" As They Deal with Urban Decay?

In the US, the city of Schenectady, New York, was known throughout the 19th and 20th centuries as the city that "lights the world". Today, Schenectady, the home to General Electric and an award winning smart city, struggles with the problems of a shrinking city, in particular, with urban blight.[4] On average, a single blighted property can cost a municipality tens of thousands per year in direct and indirect costs. Direct costs include code violation enforcement and engineering and property maintenance. Indirect costs include uncollected taxes, devaluation of adjacent properties and impact on city services such as police and fire calls. Increasingly, studies of urban blight are looking at the impact of blight on other social and economic issues, such as public health and economic opportunity. Schenectady’s Mayor, Gary McCarthy, a former president of the New York Conference of Mayors, has a vision for fighting urban blight in his award winning, but shrinking, city. His vision is well-informed and has proven to be value generating in other cities. Unfortunately, his efforts are challenged with a shrinking budget, legacy systems, a lack of a strategic IT leader and no city-wide data management strategy or workforce. His commitment to closing the livability gap in Schenectady is driving a range of innovative public private partnerships and grant funded research designed to generate the nuanced understanding he needs to make context-specific investment decisions. He recognizes it is necessary to fully appreciate Schenectady’s context and capability and to invest not only in technical solutions to make the city smarter, but in policy and management capabilities that leverage the strengths of Schenectady, but that also reflect the changing context of the city.

Cities throughout the world, whether growing or shrinking, large or small, are looking to technologies such as sensors and IoT networks as a way to capture data about city programs and services. The idea is that new data, captured by these sensors, shared across networks and used to drive analytics will help inform policy decisions in that city. Sensors collecting data on water consumption in cities, for example, are being used to help inform routine water management operations as well as more policies. In many cases, this is possible because those cities have the capability to collect and manage large volumes of data and they have sophisticated data management capabilities. Further, they have a history of evidence-based decision making, or at the very least, they already have systematized decision-making about water resources management and can now integrate the use of new analytics into those decision-making processes. In other cities, while the deployment of sensors is technically possible, capability to organize and manage the resulting data and to make it ready and available for use in sophisticated analytics in support of decision-making is at best limited, and in many cases missing. Many shrinking cities, particularly small cities are finding that while they see the potential of machine learning to provide automated decision-making support to a shrinking workforce, for example, they don’t have the requisite volume of data or the capabilities to manage data or develop necessary technologies. Unfortunately, some cities are finding this out after significant investments are made. Money is being spent, but value creation in such cases is limited.

How policy makers in shrinking cities such as Schenectady, Sheffield and Ostrava will continue to make their cities livable is unclear. What is clear is that Mayors and urban policy makers need a more nuanced understanding of the issues facing both growing and shrinking cities and of the range of contextual conditions that influence the success of a smart city. They must use that new understanding proactively to make decisions that keep cities viable and livable.

Beyond "Universal Patterns": From Understanding Context to Generating Impact

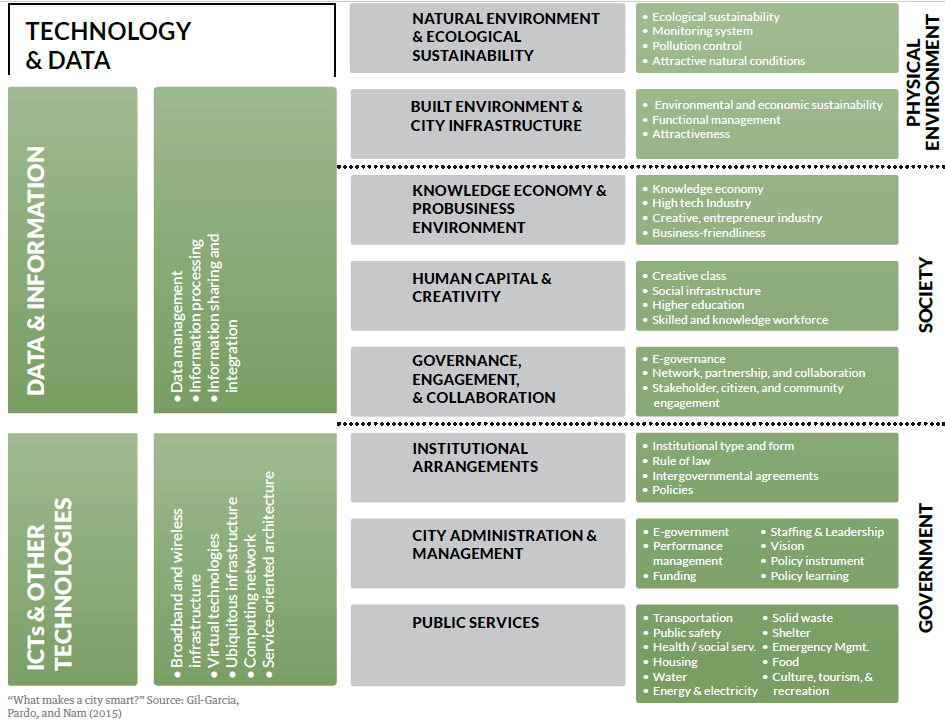

Scholars and practitioners from a range of disciplines and professions have been working to understand what makes a city "smart". They have developed models and theories, conceptualizations and frameworks, ranking systems, strategies, solutions and checklists. Early characterizations of a smart city focused on technical aspects, such as smart buildings, energy and connectivity. Smarter cities were those that made use of these technologies to save money and deliver higher quality infrastructure. These efforts, from both a research and practice perspective, generally relied on what Albert Meijer, a leading smart city researcher from the Netherlands calls, "universal patterns". One city after another, successfully adopted highly technical strategies focused on solving very technical problems. Over time however, as smart city strategies moved beyond strictly technical innovations to become more socio-technical, and encompassing such things as the delivery of social services, the more it became clear that context matters. Unfortunately, while leading researchers and practitioners are calling for more emphasis on context, they acknowledge that we don’t know enough about how context impacts outcomes. Our knowledge of the relationship between context and approaches to making cities smarter is "underdeveloped".[5] It lacks the sophistication required to provide guidance to policy makers based on nuanced understanding about how the context of their particular city is interrelated with the challenges of change.

So, today, we find ourselves in the situation where we know that context matters in smart city investment decision-making, but we also know that we need to know more about how and why it matters. We need to know how to get that insight and use it to guide the very expensive decisions that cities are making. Over time, researchers and practitioners have evolved their understanding of what it means for a city to be smart and what it takes for a city to be smart. Today’s smart city frameworks are multi-dimensional and integrative. They are reflective of the rapid technical, social and organizational innovations that have occurred during these years. They have benefitted from continued testing and reconsideration within a wider range of contexts. A leading framework proposed in 2015 by Gil-Garcia et al[6], for example, offers a comprehensive view of smart city components and elements. Over time and through continued consideration of this framework in different contexts, and by multiple research teams, the framework has been expanded to reflect the changing view of what makes a city smart. One of the original dimensions of that framework, "environment", for example, was originally envisioned as the city government’s ability to manage and monitor environmentally related systems and actions, but today, as a consequence of changing views and new research, this framework now incorporates the extent to which a city is considered environmentally friendly. This framework, and others, now includes human capital, creativity and the knowledge economy, among others, as components of smart cities. More recently, smart governance and sustainability are receiving attention as well. These efforts show that what we understand to be a smart city reflects a range of social, institutional and organizational as well as technical innovations.

Building Smart Cities in Context-specific Ways – The Guiding Principles

Mayors and urban policy makers must build an understanding of the context of their cities and of the cities they look to for best practices. If they find a strategy in another city that they believe will be help make their city smarter, they must ask hard questions of those cities; they must understand the interrelated conditions in which that success occurred. They must look closely at the policy, management and technology capabilities that made that strategy a success and then they must look closely at their own city’s capabilities. They must answer difficult questions about whether they have the conditions necessary to make their city more livable. They must know if they have the resources to close the livability gaps in their cities, if they will adapt the innovation to their context, or if they will have to continue to look for new ideas.

To transform the world’s cities into smart cities that are ready to meet changing realities caused by population increases and decreases, mayors and urban policy makers must follow these three steps:

1) Recognize the importance of context, and acknowledge that what worked elsewhere may not work here,

2) Create capability to understand context, by assessing the available knowledge and skills and building capacity where needed,

3) Use that understanding to make investments that are relevant to, and create value within, that specific context.

In other words, they must focus on the unique needs and capabilities of their cities. The process of becoming a smarter city might need to start with asking questions about the current government workforce. Is the workforce shrinking or does it need to grow? Does the workforce have the knowledge and skills necessary to adapt innovative ideas that have worked elsewhere? The point isn’t to avoid innovation, but rather to increase readiness to innovate successfully by building understanding of the particular livability gaps facing a city, the source of those gaps, and how the context of a city will interact with strategies designed to close those gaps.

Policy makers must look internally to see what problems matter more and make decisions that are locally relevant and context specific. To make a city smarter, to create value for those who live and work there, urban policy makers must understand the relationships among the context of the city, the characteristics of the problems in that city, and the characteristics of the innovations that are being considered as solutions to those problems. They must use that understanding to inform smart city investment decisions.

To put nuanced understanding of context at the center of smart city investment decisions, urban policy makers must:

- Look globally for inspiration; but look locally to see what matters most to the people in your city.

- Look globally to see what is doable; but look locally to see what’s reasonable in your city.

- Look locally to understand the source of and nature of pressures on your city. What is the context of your city and how is it impacting and interacting with the pressures on your city?

- Look globally to see how the world’s leading cities are responding to new pressures from urbanization and de-urbanization, but look closely at what makes those smart city innovations possible in that place and at that time. Ask yourself, will that work here? If not, what must you change to make it work in your city? Finally, you must decide, is it worth it?

- Build partnerships with smart cities researchers to help build an understanding of the impact of context how to understand your local context better.

As the world around us changes and those changes create new and complex problems, policy makers must recognize the need for a deeper understanding of the specific context of cities and resist the temptation to fast track by defaulting to generic, universal patterns of innovation. Urban policy makers seeking to increase public value through innovation must work in partnership with researchers and practitioners to shed new light on how context matters for their cities and citizens. These leaders must learn how a lack of attention to context is making it difficult for their cities and their partners to respond quickly and effectively to the increasing challenges caused by massive shifts in the distribution of the world’s population from rural to urban areas and from small urban to large urban areas. The cost of not learning these lessons is that investments in innovations of all kinds are being made even when the context necessary for value to be created through those investments is missing.

Theresa Pardo is Director of the Center for Technology in Government and a Full Research Professor of Public Administration, University at Albany, SUNY. Read full bio here.

Endnotes:

[1] Livable City: https://www.livablecity.org/missiongoals/

[2] "In an urbanizing world, shrinking cities are a forgotten problem", Biswas, Tortajada and Stavenhagen: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/03/managing-shrinking-cities-in-an-expanding-world

[3] As Rural Towns Lose Population, They Can Learn To ‘Shrink Smart’: https://www.npr.org/2018/06/19/618848050/as-rural-towns-lose-population-they-can-learn-to-shrink-smart

[4] Urban decay: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urban_decay

[5] Smart City Research: Contextual Conditions, Governance Models, and Public Value, Meijer, Bolivar and Gil-Garcia, 2015; https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439315618890

[6] "What makes a city smart?" Gil-Garcia, Pardo, and Nam, 2015: https://content.iospress.com/articles/information-polity/ip354

Smart Cities.. The Policy Catalyst for Sustainable DevelopmentAugust 7, 2020 6:59 pm

[…] clear. When smart cities fail, they create expensive lost opportunities for development, and may lead to urban and social decay (Pardo). However, assessing if they are succeeding and measuring their performance towards the […]