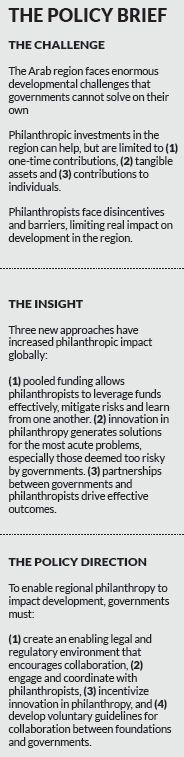

The Arab world has long suffered from a wide spectrum of socio-economic challenges and conflicts. Three statistics demonstrate these acute challenges beyond doubt: 1) two-thirds of the region’s population is either poor or vulnerable to multi-dimensional poverty, 2) the region’s youth unemployment rate has hovered at almost 30% for two decades with no progress, remaining the highest in the world, and 3) it produces 32% of the global population of refugees and 38% of the global population of internally displaced people, while accounting for only 5% of the global population, causing severe consequences for their future and the future of the region. How can we change this?

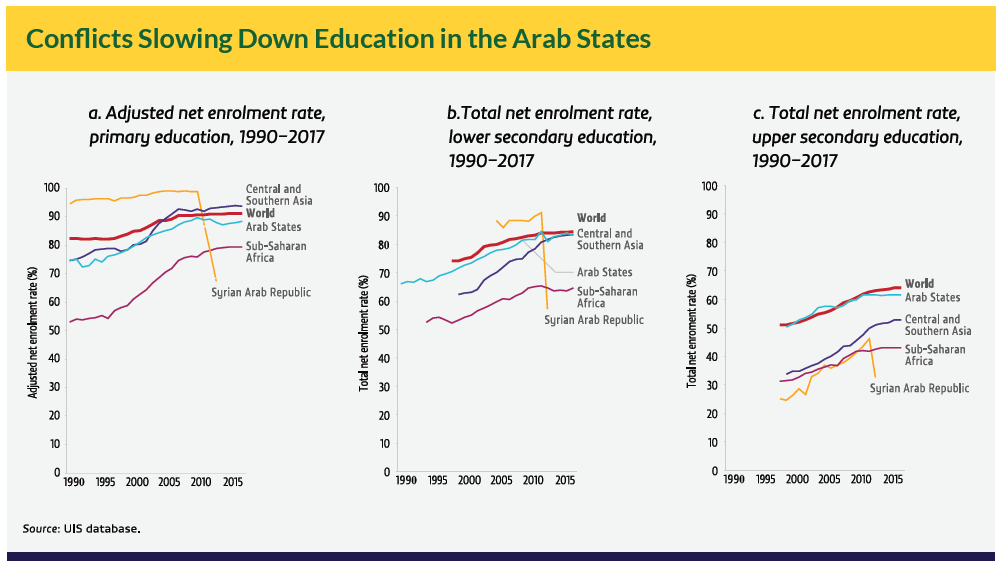

The urgency of addressing the short and long-term impact of the region’s humanitarian crises cannot be overstated. The Arab region must begin investing more effectively in human development and governments simply cannot do it alone. Massive resources are needed just to recoup the losses in development overall. Taken alone, recouping the loss in education is a mammoth undertaking that requires extensive resources.

Source: UNESCO[1]

There is no doubt that the largest investment will and should continue to come from national governments themselves. International assistance is also needed to mitigate the impact of conflict on poorer countries. At the same time, in a region historically blessed with a culture of philanthropy, philanthropic investment needs to be better mobilized alongside government resources to address the biggest development challenges the region is facing.

The Limited Impact of Philanthropy in the Arab World Today

While the vast majority of philanthropists continue to donate to traditional charitable causes through religious institutions or arms length state organizations, a smaller but important number of high net worth (HNW) philanthropists are looking for new mechanisms to contribute. Engaging them is critical to unlock potentially large amounts of strategic philanthropic investment and gear it towards addressing chronic developmental goals. Not to do so would give credence to their reasonable argument that the Arab philanthropic ecosystem is not well developed and prohibitive of any meaningful processes of change.

The consequence of the dissatisfaction of Arab HNW philanthropists with the current philanthropic ecosystem is that many end up limiting their contributions to outside of the region, resulting in precious lost opportunities for development. Their reasoning varies, but they are often drawn to associations with renowned organizations or hope for higher impact, greater recognition or even easier processes. This is evident by the number of donors who have given large donations to some of the best universities in the world, where prominent buildings have been named after Arab donors, but with fewer similar examples within the region itself.

Among Arab HNW philanthropists, who have contributed within the region, many deploy three approaches that do not yield high impact results: 1) limiting contributions to smaller one-time campaign donations; 2) contributing tangible assets only such as university buildings or goods for humanitarian assistance; or 3) contributing to individual-level impact such as scholarships or medical relief.

These three common approaches are often encouraged and recognized by government leaders, but much higher philanthropic impact towards overcoming developmental challenges can and should be expected in the Arab region.

At the moment, very few Arab HNW philanthropists have attempted to contribute to solving large-scale challenges. However, if given the opportunity, Arab HNW philanthropists, not unlike their global peers, would want to use their philanthropic contributions to help solve some of the region’s and the world’s biggest and most pressing problems. One successful example is the Saudi philanthropist Mohammed Abdul Latif Jameel. His endowment of the MIT-based Jameel Poverty Action Lab has been instrumental in creating a revolution in evaluation by applying behavioral economics to global development. However, for this to be replicated at-scale, changes are necessary to draw and support these HNW philanthropists in overcoming these challenges.

How Philanthropy Can Impact Data-Driven Policy: The Case of J-PAL

In 2005, the MIT Poverty Action Lab was renamed Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) following a major contribution to its endowment by philanthropist and MIT alumni Mohammed Abdul Latif Jameel. J-PAL is a global research center working to reduce poverty by ensuring that decisions related to scaling programs and shaping policy are informed by rigorous data. The objective of J-PAL is to conduct randomized evaluations to determine the effectiveness of poverty-alleviation programs.

The Lab affiliates have led more than 800 randomized evaluations in over 80 countries across a diverse range of topics, from clean water to microfinance to crime prevention. The research group at J-PAL helps create the infrastructure necessary to support affiliates’ research around the world.

Today, J-PAL’s affiliate network has grown to include 194 professors using randomized evaluations to answer critical questions in the fight against poverty. The initiative is now supported by many donors in addition to Community Jameel; a social enterprise organization, including foundations such as Egypt-based the Sawiris Foundation, The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Google.org, as well governments including Australia and the United Kingdom.

These investments have helped J-PAL reach more than 400 million people worldwide through conducting and sharing research findings; influencing the policy of partner governments and approaches of non-governmental organizations; and educating and training policymakers.

In the Arab region, J-PAL’s Middle East & North Africa (MENA) Initiative’s work spans a wide range of sectors. They focus on issues of high priority to policymakers in the region, including employment, access to finance, refugees and their host communities, and social protection. They partner with researchers from regional universities and collaborate with NGOs, foundations, and governments to help build a culture of evidence-informed decision-making in the region. They also conduct capacity-building activities for policymakers, researchers, and academics seeking to learn and apply rigorous impact evaluation methods.

Three New Approaches to Collaborative Philanthropy in the Arab World

I – Encouraging Pooled Funding

Globally, HNW philanthropists are still learning and experimenting with different approaches to tackle some of the most persistent challenges in every sector. Pooled funding has allowed many philanthropists to leverage their funds from other donors (public and private), mitigate risk and be part of a learning community.

Even leaders at The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which gives away more money on an annual basis than any other foundation in the world, recognize that it needs to work in collaboration with other donors in order to achieve its goals. They shrewdly and actively galvanize other HNW donors to contribute through The Giving Pledge; a global campaign to encourage extremely wealthy individuals to contribute a majority of their wealth for philanthropic causes.[2] The foundation has also supported the creation of several pooled funding initiatives such as The END Fund and Co-Impact. Many other foundations and philanthropists have followed suit, indicating that we will see more and more philanthropists opt for pooled funding. It is estimated that pooled funds could become the catalyst for more than $5B in annual giving.[3] One pooled fund, Blue Meridien by the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, started in 2016 with $750M and has grown to $1.7B in 2019 with a group of donors.[4]

While the Arab world have long had pooled funding models such as Taawon known as The Welfare Association for Palestine or AlMakassed Philanthropic Islamic Association of Beirut, it is still far from a common practice outside of governmental or religious funds. However, that may be changing with new momentum giving way to promising examples of regional leadership.

The Shefa Fund, founded by Khaled and Olfat Juffali in 2013 is a pooled fund that focuses on improving the health of vulnerable children and families in the Middle East and Africa. The Shefa Fund provides large grants for high impact health issues that are under-funded in the region, such as polio and neglected tropical diseases. The size of the Shefa Fund is still relatively modest against the need, but, in only a few years, it has proven that the model is feasible and has the potential to grow.

Solving Chronic Healthcare Challenges through Pooled Funding – The Case of Shefa Fund

Khaled and Olfat Juffali established the Shefa Fund in 2013 to create a community of collaborative donors who are committed to improving the health of vulnerable children and families in the Middle East and Africa.

The Shefa Fund focuses on contributing to reducing the large gap in funding for neglected tropical diseases.

The basic premise of the Shefa Fund is that by working together donors can have a bigger impact. In order to facilitate the collaborative process, they set a screening and grant selection process with a small number of donors and work closely with international organizations, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, to learn from their extensive experience.

Since 2013, the Shefa Fund has supported 11 projects with a total value of grants of over $11M impacting the lives of over 16 million people. In that period, they have drawn on funding from 20 donors with each contributing a minimum of $250 K.

Shefa has provided grants to organizations that have a well-established presence in the region. Grantees have included The End Fund, Nothing But Nets and International Medical Corps.

They also fund organizations that provide health care services and vital supplies to vulnerable women and children, following natural disasters or conflict.

The success of the Shefa Fund and recent contributions by Arab HNW philanthropists to global pooled funds present an opportunity to capitalize on growing interest and recognition of the relevance of this model for the region.

In addition to leveraging funds, pooled funds are effective at drawing on donor resources – everything from geographical presence to expertise and infrastructure. They also test the potential solutions at a larger scale by adopting common approaches among a wider group of donors.

In the Arab world, at least three types of developmental responses lend themselves well to pooling funds – post humanitarian assistance to refugees, youth skills development and employment and environmental protection and sustainable resource development.

Many other issues could also benefit from pooling funds; however, these three issues share two factors that make them particularly ripe for combining efforts and resources: 1) they are very complex issues that no one country is able to address alone, therefore combining resources and efforts is essential to developing scalable solutions; and 2) the negative consequences of these issues not being addressed have spillover effects not bound by borders. Similarly, the benefit from finding solutions to these three issues would have high returns for every country in the region in the form of greater stability, more talent for economic growth and preventing further environmental erosion and catastrophe.

II – Incentivizing Innovation

In addition to pooling funds, governments need to recognize the important and different role that philanthropy can play in investing in new and innovative solutions to big challenges. While governments cannot afford to take risks with public funds, private philanthropists are perfectly suited to invest in new ideas, test alternative approaches and pilot untested models.

Arab HNW philanthropists are increasingly demanding better tracking and measurable results against their donations. Yet, despite this positive development, most funding is still largely invested in traditional approaches that perpetuate short-term band-aid solutions rather than new approaches that could provide entirely different ways of thinking about challenges or address issues at their root cause.

Arab governments would do well to incentivize greater philanthropic contributions in finding innovative solutions to some of the region’s biggest challenges rather than fill gaps. This is not a wholesale invitation for philanthropists to do as they please, particularly when their interventions may affect vulnerable populations or public goods. Philanthropic innovation should not be allowed to do any harm, but it should test assumptions and break boundaries. Their focus should be on investing in approaches that may have a higher risk of failure, but have the potential to create real change.

Despite many failed or misguided philanthropic investments, it is an exciting time to explore new possibilities for philanthropic activity. Philanthropists can invest in different stages of innovation from sourcing new ideas, to supporting grantees who are taking a high-risk approach, to funding the scaling of initiatives that worked on a small scale.

How Can Innovative Philanthropy Create Impact?

Innovation has become an overused term and could imply many different things. In the context of philanthropy, it could vary from investments in research that leads to significantly better results, a new invention such as a vaccine or an affordable source of energy, or a new scalable and sustainable financing mechanism to deploying technology to accelerate progress on education. Some successful examples include the following:

The X Prize provides sizeable awards to solve specific challenges.[5] A $10M prize is currently being offered for teams to develop technology that surveys biodiversity and helps protect rainforests worldwide.

Omidyar-funded Give Directly – an organization that provides direct cash assistance to the world’s poorest and is currently piloting a project supporting universal basic income to 26,000 people in Kenya.[6]

NewProfit uses venture philanthropy to invest in organizations with promising ideas. They provide growth capital, strategic advice and capacity development.[7]

Innovations in philanthropy are feasible, offer greater benefit for the region and should be incentivized by government. Governments interested in attracting innovation in philanthropy need to revise philanthropic legal frameworks to ensure that such entities can register and operate in the region without debilitating restrictions. They should also encourage and recognize efforts that experiment with new approaches through engagement, profiling and awards.

III – Better Partnership with Government

Of all the potential collaborations needed for more effective philanthropic investment, none is more important than partnerships with governments.

Governments and philanthropists have not always had the most natural relationship. Government organizations sometimes view philanthropists as encroaching on their mandate while philanthropists may view government as dictating fund allocation, or worse, as a source of gaps philanthropists are expected to fill.

In recent years in the US for example, philanthropy has drawn much scrutiny following a number of incidents related to failed, disruptive and large-scale interventions. Low philanthropic disbursements against tax credits and philanthropists using charitable causes to launder their image has also caused concerns.

The above issues have not played out in the same way in the region in large part because of the lack of donors operating at the same scale. Some of the issues, such as tax credits for donations are also not entirely relevant. However, despite the scrutiny and barriers to addressing large-scale issues in countries like the US, UK and Europe, the vast majority of foundations, including some founded by Arabs, find those ecosystems more conducive to basing and operating their foundations. Some of the biggest reasons include the clearer legal frameworks, ease of registration and flexibility around operating models, including pooled funds and innovation.

Philanthropy in the Arab region requires proper regulation, transparency and accountability but it also requires flexibility, incentivization and a better relationship with government. More open dialogue and joint exploration of challenges would go a long way to create an entry point for further collaboration.

Policy Directions for Philanthropic Impact in the Arab Region

As the potential impact of more strategic and innovative philanthropy in the Arab region grows, it is clear that there is much to gain from more collaborative approaches both within the private philanthropic community and with government. Governments can play an important role through more conducive policies, open-dialogue, incentives and guidelines.

First – Create the Enabling Environment

Governments need to create an enabling environment for regional philanthropy to flourish. Importantly, they need to remove barriers for collaboration among donors.

Today, most Arab countries do not have policies that allow for creating pooled funding managed by donors themselves, leading Arab donors to set up pooled funds abroad or to participate in global pooled funds only.

Arab governments that have updated their laws around donations and have enabled private foundations to register should now take the next step to devise a clear policy and mechanism for pooled funding with strong accountability and transparency requirements for receiving and disbursing funds.

Governments should study examples of global funds successful at attracting private and public funding and gearing them towards pressing development challenges with a view to eventually collaborating with high impact philanthropic pooled funds within the region.

Second, Open Dialogue with Philanthropists

Governments should invest in better dialogue and coordination with philanthropists. Some of the largest aid agencies and even municipal level governments have set up facilities to interact with philanthropists.

Government could consider creating hubs (at city level and national level) for philanthropic dialogue, information sharing and support in every Arab country in the region.

Open communication with philanthropists will lead to a better understanding of how foundations operate, their goals, the challenges and opportunities facing them and how the regulatory environment could respond.

Government hubs for philanthropy should not attempt to regulate dialogue among philanthropists but rather should help facilitate access to necessary information to enable the success of philanthropic investment. This would include access to data, government expertise and decision makers.

At the same time, government can also encourage sharing of lessons learned, resources and expertise that philanthropists have to offer.

Over time, these centers may evolve into hubs for centralized coordination for public-private partnership.

Third, Nurture Innovation in Philanthropy

Governments should incentivize innovation in philanthropy. Incentivizing innovation in philanthropy is, in large part, about creating an enabling environment for philanthropy at large. Without an enabling environment, philanthropists will not be encouraged to move outside of traditional models of giving.

Governments could also encourage innovation in philanthropy by rewarding and recognizing philanthropists who invest in finding new solutions to big challenges. It could do so in multiple ways including providing limited matched seed funding or space in which to test out a model in close cooperation with a government body.

Government should also work closely with the philanthropic sector to develop new regulatory frameworks for new approaches to giving, such as online collection and disbursements of funds – an under-developed area in the region.

Fourth, Develop Partnerships

Arab governments should collaborate to develop voluntary guidelines for collaboration between foundations and governments with the objective of improving investment outcomes on big regional challenges. One successful example to follow, is in the OECD Guidelines for Effective Philanthropic Engagement .[8]

A similar effort could be spearheaded in the region to develop voluntary guidelines through a collaborative and focused dialogue between government, foundations, philanthropists, non-governmental organizations and universities in the region.

The international trend towards greater philanthropic collaboration coupled with greater interest within the region is an opportunity to contribute to bigger and more sustainable funding for the greatest challenges in the region, creating engaged learning communities and ramping up scale.

Collaboration cannot be forced but it can be encouraged, incentivized and supported. Policymakers across the region should strive to do so if they want to reap the benefits of collaboration with Arab philanthropists who are able to contribute substantially.

Maysa Jalbout is a leader in international development and philanthropy. She is currently a Visiting Scholar and Special Advisor on the SDGs at MIT and ASU and a Non-resident Fellow at the Brookings Institution. Read full bio here.

Endnotes:

[1] Arab States 2019 Global Education Monitoring Report (UNESCO): http://gem-report-2019.unesco.org/arab-states/

[2] The Giving Pledge: https://givingpledge.org/

[5] X Prize: https://www.xprize.org/

[6] Give Directly: https://www.givedirectly.org/about/

[7] New Profit: https://www.newprofit.org/

[8] OECD Guidelines for Effective Philanthropic Engagement were developed together with the Worldwide Initiatives for Grantmaker Support (WINGS), the European Foundation Centre (EFC), UNDP, Stars Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/site/netfwd/ENG%20-%20Guidelines%20for%20Effective%20Philanthropic%20Engagement%20country%20pilots.pdf

You must be logged in to post a comment.